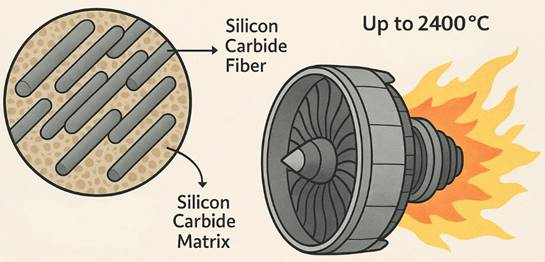

Ceramic Matrix Composites (CMCs) are a class of high-temperature materials engineered to marry the heat tolerance of advanced ceramics with the toughness of composites. A typical CMC, like silicon carbide fiber in a silicon carbide matrix (SiC/SiC), can withstand temperatures hundreds of degrees hotter than metal alloys while being only a fraction of the weight [[1]] [[2]]. This combination is revolutionary for industries where operating temperatures and weight directly translate into performance and efficiency gains. For example, jet turbines with CMC components can run at ~2,400 °F (∼1,315 °C)—up to 300–500 °F hotter than the best superalloys—enabling higher engine power and efficiency [1] [[3]]. CMC parts are also about one-third the density of nickel alloys, which means significant weight savings without sacrificing strength [1] [3]. In short, CMCs allow engineers to push beyond the “headroom” left in metals [3] and venture into regimes once thought off-limits except to brittle ceramics or ablatives. Today these materials are transitioning from decades of R&D into critical applications in aerospace, defense, and energy. The following sections trace the innovation journey of CMCs – from the initial vision of toughened ceramics, through early setbacks and dormant research, to the recent breakthroughs that have made CMCs a commercial reality.

The Pain Point: Legacy Materials Hit a Wall

High-temperature machines – from jet engines and rocket motors to gas turbines and re-entry vehicles – have long been constrained by the limits of conventional materials. Nickel-based superalloys have been the workhorse for turbine blades and combustors, but even these advanced metals reach a point of diminishing returns. In modern gas turbines, first-stage metal shrouds and blades require elaborate cooling schemes and thermal barrier coatings to survive ~1,600 °F (870 °C) gas temperatures, and even then the metal itself is usually limited to around 920 °C before mechanical properties degrade [[4]]. Pouring cooling air through metal components wastes energy – air used for cooling is air not used for combustion, imposing an efficiency penalty [4]. The material limits of nickel alloys have essentially become a heat barrier to better performance. As one GE engineer put it, “we’re running out of headroom in metals” [3].

Moreover, metals are heavy. Superalloy turbine parts have densities on the order of 8–9 g/cc. This weight not only diminishes fuel efficiency in aerospace but also adds enormous stress on rotating machinery. Designers compensate with lighter designs and hollow air-cooled parts, but these add complexity and cost. Even exotic refractory metals (tungsten, tantalum alloys) can take higher heat but are impractically dense and often brittle or difficult to process.

On the other end, monolithic technical ceramics (like solid SiC, alumina, zirconia) can handle extreme temperatures far beyond metals – but they are catastrophically brittle. A tiny flaw or thermal shock can cause a ceramic blade or panel to fracture suddenly [[5]]. Early attempts to use monolithic ceramics in engines (e.g. ceramic turbine blades in the 1980s) failed because cracks and impacts could not be tolerated; the lack of fracture toughness was a showstopper. As experience with glass and ceramics had taught aerospace engineers, these materials “fracture with ease” under mechanical or thermal-mechanical loads, akin to how glass shatters under stress [5].

Thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) on metals and ablative composites were stop-gap measures. Coating a metal part with a ceramic (e.g. yttria-stabilized zirconia on turbine blades) extends its life by a few hundred degrees, but coatings can spall off and they don’t fundamentally change the metal’s temperature limit – they only delay it. Ablative heat shields (like carbon-phenolic composites on re-entry vehicles and missiles) can survive extreme heat by sacrificing material: they char and erode away carrying heat with them. But ablatives are one-time use (needing replacement or refurbishment) and add mass and thickness. For reusable systems or long-life components, ablation is not an ideal solution [[6]].

Nowhere were these pain points felt more acutely than in next-generation aerospace and energy applications:

- Jet engines (Aerospace): To improve fuel efficiency and thrust, engines must run hotter. Yet by the early 2000s, metal turbine inlet temperatures were plateauing because even cooled single-crystal superalloys approached their limits. Engineers resorted to bleeding 20–30% of compressor air for cooling passages [4], sacrificing efficiency. Combustors, limited by metal cooling, also couldn’t run the ultra-lean burn needed for low emissions (NOₓ formation) – a metal liner with film cooling consumes so much air for cooling that there’s not enough for fully premixed lean combustion [4]. A material that could withstand flame temperatures without cooling promised a double win: higher engine efficiency and cleaner combustion [4].

- Hypersonic flight and re-entry (Defense/Space): Vehicles traveling at Mach 5+ or returning from orbit see skin temperatures well beyond 1,500 °C (2,732 °F) for extended periods [5]. No metal can survive these conditions without either melting or softening dramatically. Historically, the only solution was carbon-carbon ablative composites (e.g. the Apollo capsule heat shields, or the Space Shuttle’s reinforced carbon-carbon leading edges) which can survive high heat but oxidize if exposed to air and must be protected or used only once. Hypersonic glide vehicles and reusable spacecraft have a dire need for materials that handle 1,500–2,000 °C while bearing loads and not burning up [[7]]. As one hypersonics engineer noted, without advanced CMC materials, designers are forced back to ablatives: “If we didn’t use CMC, we’d need an ablative [thermal protection] that vaporizes during reentry,” adding weight and cost for each mission [6].

- Industrial Gas Turbines & Energy: Land-based turbines for power generation also push for higher firing temperatures to boost efficiency (e.g. combined cycle plants). But unlike aircraft engines, power turbines demand tens of thousands of hours of part life and are extremely cost-sensitive. Metals hit a wall here too – parts can’t simply be swapped every few hundred hours if you want economic power generation. In the 1990s, the U.S. Department of Energy identified CMC liners and shrouds as a key enabler for hotter, cleaner-burning gas turbines without needing excessive cooling air, which in turn could dramatically cut NOₓ emissions and improve efficiency [4]. However, the reliability standards in this sector are even more stringent, and early ceramic parts did not yet inspire the needed confidence.

In sum, by the late 20th century, engineers were caught between a rock and a hard place: metals were maxed out, but monolithic ceramics were too fragile. The performance demands of modern aerospace and energy systems were creating a conspicuous materials gap. What was needed was a material that combined the best of both – the heat capabilities of ceramics with damage tolerance more like metals. That is exactly the promise that ceramic matrix composites eventually fulfilled.

Scientific and Technological Foundations: Toughening Brittle Ceramics

The concept of reinforcing a brittle ceramic to prevent catastrophic failure has its roots in materials science efforts of the 1960s and 70s. Traditional ceramics like alumina or silicon carbide have high hardness and can survive high heat, but their fracture toughness is very low – akin to glass, they snap once a crack starts [5]. Early approaches to toughen ceramics included adding secondary phases like whiskers or platelets of another ceramic dispersed in the matrix. For example, in the 1970s researchers added silicon carbide whiskers to alumina cutting tools. These whisker-reinforced ceramics showed some improvement in crack resistance, but it was modest – enough for niche uses (e.g. ceramic cutting inserts) but not a game-changer for structural applications [5]. The improvement was limited because the whiskers were still short and the crack only had to circumvent small obstacles before causing failure.

A more radical idea was to use continuous fibers to reinforce ceramics, taking inspiration from fiber-reinforced plastic composites (which were booming in the aerospace industry by the 1970s). If tiny glass or carbon fibers could dramatically toughen plastics, could ceramic fibers toughen ceramics? The challenge was finding any fiber that could survive high temperatures and embed in a ceramic matrix. Early work used carbon fibers in ceramic or glass matrices – essentially creating a carbon-fiber reinforced glass. Carbon fibers have excellent strength-to-weight and can handle moderate heat, but they oxidize above ~500 °C in air [7], making them unsuitable for very high-temperature use unless sealed from oxygen.

A significant breakthrough came from Japan in the mid-1970s: inventing an affordable silicon carbide fiber. In 1975, scientists led by Dr. Seiji Yajima developed a method to create continuous SiC fibers by pyrolyzing an organosilicon polymer (polycarbosilane) into ceramic form [[8]]. This was transformational – silicon carbide has very high thermal stability and does not melt until ~2,800 °C, and now one could have it in fiber form. By 1983, Nippon Carbon commercialized these SiC fibers under the trade name Nicalon™ [8]. The first-generation Nicalon fibers had high tensile strength and could be woven into fabrics or mats, though they contained some oxygen and were partly amorphous (which limited their top-use temperature to ~1,200 °C). Even so, this development provided the essential ingredient for CMCs: a ceramic fiber with usable flexibility and strength.

Researchers quickly realized that incorporating continuous fibers (carbon or SiC) into ceramic matrices could drastically improve crack resistance and thermal shock tolerance [5]. When a crack forms in the ceramic matrix of a CMC, the fiber reinforcement can bridge the crack, bearing load and preventing sudden propagation. Instead of a brittle fracture, the composite can exhibit pseudo-ductile behavior: the crack may spread locally in the matrix, but fibers either deflect it or pull out, absorbing energy without fracturing completely [2] [5]. This “fiber pull-out” mechanism (visible as fibers dangling from a crack surface) is the key to CMC toughness – it’s what allows CMCs to fail gracefully like a metal (which yields) rather than shattering like a ceramic [2] [5].

By the late 1970s and 1980s, laboratories in the U.S., Europe, and Japan were fabricating the first true ceramic matrix composites. Two material systems in particular emerged:

- Carbon Fiber/Carbon Matrix (C/C): Essentially carbon-carbon composite, this was actually an earlier development used in extreme applications like missile nose tips and re-entry vehicle heat shields in the 1960s [[9]]. Carbon-carbon can survive short bursts to well over 3,000 °C (in inert or vacuum conditions) and was famously used on the Space Shuttle’s nose cap and wing leading edges in the 1980s, where it sees ~1,500 °C during re-entry [5]. C/C has excellent thermal shock resistance and doesn’t melt, but its achilles heel is oxidation – in atmospheric use it must be protected (e.g. Shuttle C/C leading edges had a thin silicon-carbide coating to reduce oxidation). Carbon-carbon is a subset of CMC technology and proved the general concept that composites could handle high heat, but for air-breathing engines running continuously, pure carbon fiber wasn’t a long-term solution due to oxidation.

- Silicon Carbide Fiber / Ceramic Matrix: With the advent of SiC fibers, efforts turned to SiC/SiC composites and related systems (e.g. carbon fibers in SiC, or SiC fibers in glass-ceramic matrices). Research groups like SEP in France and NASA/Air Force in the U.S. conducted trials. One approach was chemical vapor infiltration (CVI) to form a SiC matrix around a fiber preform; another was melt infiltration of silicon into a carbon or SiC preform (pioneered by GE). By the mid-1980s, lab-scale SiC/SiC CMCs demonstrated impressive high-temperature stability in tests. In fact, the French SEP program was so encouraged that they built CMC nozzle flaps for a jet engine and even flight-tested a CMC exhaust nozzle at the Paris Air Show (on a Mirage fighter) in the 1980s. This was a landmark demonstration that a ceramic composite could survive real engine conditions (at least for a while). European engine models (Snecma M53 and M88, and the multinational EJ200 for the Eurofighter) all had development programs exploring CMC parts in the 1980s [4].

- Oxide-based CMCs: In parallel, some focused on oxide fiber/oxide matrix composites (e.g. alumina fibers in mullite or aluminosilicate matrix) for slightly lower temperature use. These have the advantage of inherently excellent oxidation resistance (being entirely oxides) and were easier to fabricate (often via slurry infiltration and sintering). Germany’s Dornier, for example, developed an oxide CMC using Nextel™ alumina-silica fibers in a mullite matrix, and actually fielded several CMC exhaust components on turboprop aircraft in the 1980s. Those parts saw service in hot exhaust streams and proved that even a relatively brittle oxide composite (strength ~120 MPa) could function in a real engine environment [4]. The downside was that oxide CMCs couldn’t reach the ultrahigh temperatures of SiC or C/C, and the available oxide fibers would creep or degrade above ~1,000 °C. Still, this work expanded the knowledge base and showed that ceramic composites could be made reliable in at least some applications.

Underpinning all these developments was fundamental science on how to make brittle+brittle equal tough. Researchers discovered that the fiber-matrix interface was crucial. If the fiber bonded too strongly to the matrix, cracks would just tear right through fibers (leading to brittle failure). The breakthrough was realizing the fiber surface needs a weak, slip layer – a coating (often carbon or BN) that lets the fiber debond and pull out when stressed [2] [9]. This is analogous to putting a thin lubricant between fiber and matrix: it sacrifices some initial stiffness, but when a crack hits, the coating fails in shear before the fiber breaks, allowing the fiber to disengage gradually and absorb energy. Early experiments used pyrolytic carbon coatings on fibers, which worked to some extent but could oxidize. In the late 1980s, boron nitride (BN) coatings were introduced as an oxidation-resistant interphase for SiC fibers. The BN proved highly effective – it’s like a Teflon sleeve on the fiber that forces cracks to change direction and blunts their impact on the fiber. This interface engineering was a subtle scientific advance, but it made all the difference in achieving metal-like toughness in a CMC [2].

By the early 1990s, the key ingredients for modern CMCs were in place: high-strength SiC fibers (the first generation of Nicalon, soon followed by improved versions like Hi-Nicalon™ and Tyranno™ fibers), fiber interface coatings (BN, carbon), and multiple matrix fabrication methods (CVI, polymer infiltration and pyrolysis (PIP), melt infiltration, etc.). In lab settings, CMCs could be made that survived 1,200–1,400 °C with fracture toughness an order of magnitude better than monolithic ceramics. This hinted at a revolution in materials – if these composites could be scaled up and if someone was willing to bear the cost to use them.

However, moving from lab demos to practical use proved nontrivial. Early CMC components still had issues: environmental durability (e.g. SiC composites in steam or combustion gases started to oxidize or “recede” due to silica scale volatilization [5]), high manufacturing costs, and variability in quality. These hurdles meant that through the 1980s, CMCs remained mostly confined to R&D programs and a few niche military uses. The science was promising, but the technology had not yet coalesced into a clear commercial winner. That transition would require both technical breakthroughs and a strong market pull – forces that started gathering in the 1990s and 2000s.

Dormant Seeds: Early Breakthroughs That Bided Their Time

Throughout the late 20th century, CMC technology advanced in fits and starts, often ahead of its time. Many early research successes did not immediately translate into widespread use, but they laid vital groundwork that paid off later when conditions were right.

A case in point: the French SEP CMC nozzle program in the 1980s. As noted, SEP (Société Européenne de Propulsion) had developed SiC/SiC composites and even demonstrated a jet engine nozzle made of CMC [4]. They invested in scaling up production for fighter engines (Mirage and Eurofighter classes). But this bold effort hit a wall – engine tests revealed unanticipated environmental degradation of the CMC parts [4]. Specifically, SiC composites suffered from oxidation embrittlement in the presence of high-temperature steam and oxygen (a phenomenon later understood as “active oxidation” or silica scale volatility in water-rich exhaust [5]). The result: the CMC components didn’t meet durability expectations. Confidence in the material was undermined, and the program was essentially shelved in the early 1990s [4]. The French and European engine builders pulled back, concluding that CMCs weren’t ready for prime time. This could have been the end of the story, but it was really just a hibernation. The knowledge from that program – about fabrication, what worked and what didn’t – would resurface later. In the meantime, CMC R&D in Europe went quieter for a while after that setback.

The United States also had early forays that remained under the radar for years. The U.S. Air Force and NASA experimented with CMC components in the late 1980s and 90s for military engines. Notably, carbon-ceramic flaps and seals were tried in the exhaust of the F414 jet engine (used in F/A-18E/F Super Hornets). In one program, an oxidation-protected carbon matrix composite (C/C with SiC fibers and a SiC coating) was developed, resulting in engine exhaust seals that lasted 9X longer than metal ones. By 1995, thousands of engine hours had been logged on F414s with these CMC exhaust parts [4]. This was a quiet success – a CMCs in service on a frontline fighter jet, improving durability. Yet, outside of defense circles, few realized this milestone. The technology remained a bit niche and classified, and it did not immediately spur a broader commercial adoption. It was like a proof-of-concept hiding in plain sight: the military demonstrated that CMCs could work and last in a harsh engine environment, but commercial aerospace was not yet feeling enough pain to take the risk.

Meanwhile, NASA and DOE programs in the 1990s sowed seeds that only later found sunlight. The Department of Energy launched the Continuous Fiber Ceramic Composite (CFCC) program (circa 1992–2002), investing about $10 million per year to foster CMC technology for energy applications. This program funded national labs (Oak Ridge, Argonne) and companies (AlliedSignal, DuPont, GE, etc.) to develop various CMC systems and understand their behavior [2]. They achieved remarkable scientific progress – for example, ORNL researchers (Lowden, Lara-Curzio, et al.) pinpointed the mechanisms of fiber/matrix interface degradation and recommended switching from carbon to BN coatings, which industry adopted widely. They also developed improved processes like a faster CVI method to infiltrate fibers with ceramic in hours instead of months [2]. By the early 2000s, the CFCC program had culminated in several field demonstrations: one celebrated case in 1999 was a CMC combustor liner in a 170 MW gas turbine at a power plant (Malden Mills), which achieved record-low emissions and operated successfully [2]. Yet, after the program ended in 2002, there was no immediate commercial rollout of CMC-equipped turbines. The power industry, notoriously conservative, was not ready to adopt expensive new materials that hadn’t proven decades of life. So those CMC liners remained as one-off demos – shining examples of what could be, waiting for the right moment.

In effect, the 1980s and 90s produced a wealth of dormant know-how. Materials like CMCs often go through a long gestation, where early discoveries don’t find a market niche and thus lie fallow until a critical need arises. By 2000, the basic technology was proven in labs and even in select real-world tests. But the broader industries were not compelled to invest in this costly, radical change yet. It needed a push – a combination of market pressure and some final technical polish – to break out of its dormant stage.

That push came in the 2000s. Rising fuel prices, climate concerns, and new performance demands started to align with the maturity of CMC technology. The latent potential of those decades of CMC R&D was about to be unleashed, much like a long-dormant seed sprouting when the season finally turns favorable.

A Market Awakens: Demand Drives Investment

In the 2000s, several trends converged to pull CMCs from the lab into the product development pipeline. After years of lukewarm interest, market forces in aerospace and defense suddenly created a sense of urgency for materials that could outperform metals.

On the commercial aerospace side, the mid-2000s brought an intense focus on fuel efficiency. Oil prices were climbing, and airlines were desperate to cut operating costs. At the same time, environmental pressures (and future carbon regulations) put efficiency front-and-center. Engine makers like GE, Rolls-Royce, and Pratt & Whitney were pushed by airframe manufacturers and airline customers to achieve double-digit percentage improvements in fuel burn. Higher turbine temperatures are one of the most direct levers to improve engine thermal efficiency. Every ~50 °C increase in turbine inlet temperature can boost efficiency a few percent. By 2005, it was clear that incremental tweaks to cooling and alloys were not enough for the leap in efficiency sought for next-generation engines (on programs like Boeing’s 787 and 737 MAX, or Airbus’s A320neo). This created a strong market pull for any material that could enable a step-change. It’s no coincidence that in the same timeframe, GE Aviation formally launched a CMC commercialization effort (around 2005–2007), recognizing that the upcoming engine programs would reward a successful high-temp composite [3]. In interviews, GE execs noted that the business case for CMCs flipped around then – fuel was expensive, and customers would pay a premium for efficiency if the material could deliver it [2].

In 2007, CFM International (the GE-Safran joint venture) kicked off development of the LEAP engine for narrow-body airliners, targeting ~15% better fuel efficiency than the existing CFM56. Achieving that in one generation was unprecedented – it clearly required new tech. CMCs quickly became a centerpiece of the LEAP design. By the early 2010s, as LEAP underwent testing, word spread that it would feature CMC turbine shroud segments in the hottest zone [2]. This would be the first-ever use of CMCs in a large-scale commercial engine, and the market took notice. Even before certification, orders poured in. By 2016 (entry into service of the LEAP on the Airbus A320neo), LEAP had over 11,000 engines on order (>$140 billion value) [2], with each engine carrying a dozen CMC shrouds. The sheer volume – eventually tens of thousands of CMC parts annually – signaled that a real market had arrived. In August 2016, the first LEAP-powered plane flew passengers, marking the moment CMCs truly “arrived” in commercial aerospace.

The defense sector likewise provided a kick. By the 2010s, an arms race in hypersonic technology was heating up. The U.S., China, and Russia were all intensively developing hypersonic glide vehicles and air-breathing scramjet missiles. The Pentagon recognized that materials were a critical limiting factor for hypersonics. Reports from defense science boards began to highlight CMCs (and even ultra-high-temperature ceramics) as enabling technologies for sustained hypersonic flight [6] [[10]]. In the U.S., DARPA and DoD launched programs like HyFly and the Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC), which funneled funding into high-temp composites for engine ducts, leading edges, and thermal protection. By the late 2010s, hypersonic vehicle prototypes were flying with CMC components (or at least, program offices were contracting companies to supply them). For example, the Silicon Valley-based Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in 2023 selected Hypersonix (an Australian startup) to provide hypersonic test vehicles, specifically noting their use of CMC/UHTCMC parts developed in partnership with DoD [6]. The prospect of Mach 5+ reusable vehicles simply mandates materials beyond metal, and this looming need injected fresh investment into CMC research (particularly for even higher temperature capabilities, like CMCs that can do 1,500–1,800 °C with advanced coatings). In essence, defense provided both funding and a proving ground – if a CMC can survive a Mach 10 glide, that’s pretty convincing evidence of its performance.

Even in the energy sector, interest reawakened. In the 2010s, as climate concerns grew, governments and companies revisited the idea that CMCs in turbines could improve efficiency and reduce emissions. Natural gas power turbines with higher firing temperatures could out-compete dirtier coal plants with better efficiency. Some manufacturers started including CMC development in their advanced turbine roadmaps. For example, Solar Turbines (a division of Caterpillar) had participated in the earlier DOE demos and continued to evaluate CMC combustors for low-NOₓ turbines. While the adoption in stationary turbines lagged aerospace, the potential market is enormous – the National Academies had noted back in 1998 that industrial power could be a bigger volume driver than aerospace if CMCs became cost-effective [4]. By the late 2010s, the power industry at least started showing up at CMC conferences again, seeing that the aerospace folks had begun to crack the cost and reliability challenges.

Commercialization programs kicked into high gear. GE, for instance, not only had the LEAP engine in production but was developing the much larger GE9X engine for Boeing’s 777X, which would include five CMC components (combustor liners, nozzles, shrouds) by design [2]. GE spent hundreds of millions building out a dedicated supply chain (more on that in the next section). Rolls-Royce and Safran, not to be left behind, also accelerated CMC R&D. Rolls-Royce tested CMC combustion liners in its Advance3 demonstrator engine in the late 2010s. Safran (the French partner in CFM) not only jointly invested with GE in fiber production, but also pursued its own CMC brake discs and nozzle prototypes. Outside of engines, companies like Boeing and Airbus started considering CMCs for auxiliary power units, heat exchangers, and other high-temp systems on aircraft, now that a supply base was emerging.

Another area of market awakening was automotive and specialty transport – for example, the continued adoption of carbon-ceramic brake discs in high-end cars and aircraft. While carbon-carbon brakes had been used in fighter jets and race cars for years, newer SiC–ceramic composite brake rotors appeared in luxury road cars, offering lighter weight and fade-free performance. This is a slightly different CMC niche (often carbon fiber in a SiC matrix for brakes), but it demonstrated that volume production is possible (today thousands of ceramic brake discs are made annually). It’s a noteworthy parallel market that matured in the 2000s and 2010s, familiarizing engineers and regulators with the idea of ceramics in safety-critical roles (braking), thus indirectly smoothing the path for other CMC applications.

By 2020, it was clear the long dormancy was over. CMCs had gone from lab curiosities to must-have materials for next-gen systems. Airlines were flying passengers behind CMC parts, defense contractors were bending physics of hypersonics with CMCs, and energy companies were dusting off old plans to use CMCs to hit emissions goals. Market pull was firmly established – now it was up to the technology to meet the moment with reliable, manufacturable products.

Technical Breakthroughs Enabling Adoption

Concurrently with rising market demand, a series of critical technical advances in the 2000s and 2010s removed the barriers that had kept CMCs from widespread use. The success of CMCs wasn’t due to a single “eureka” moment, but rather multiple breakthroughs in materials science and manufacturing that collectively made CMCs viable and affordable for industry. Here we highlight the major innovations:

1. Improved Fibers – Higher Temperature and Strength: The first-gen SiC fibers (Nicalon) had significant oxygen content, which made them start to degrade above ~1,200 °C (the fibers would coarsen and lose strength as SiO₂ formed). Through the 1990s and early 2000s, manufacturers introduced second and third-generation SiC fibers with near-stoichiometric chemistry and better crystallinity [8]. Examples are Hi-Nicalon S (by Nippon Carbon) and Sylramic® (by Dow Corning/Ube), which have much lower oxygen and can retain strength to ~1,500 °C. These fibers also have higher creep resistance and modulus [8]. The evolution of fiber properties was crucial – the newer fibers gave CMCs the ability to survive the temperatures in a turbine combustor (~1,300 °C) for thousands of hours. They also enabled the holy grail of considering CMCs for rotating parts (which face high stresses) since their creep strength was improved. In short, by the 2010s the fiber was no longer the weakest link – high-quality SiC fiber tows became a reliable commodity (albeit an expensive one) and one of the pillars of modern CMC performance.

2. Fiber Coatings (Interphases) that Last: We discussed how fiber/matrix interphase coatings (like BN) are essential for toughness. Early on, carbon was used but proved too prone to oxidation. The adoption of boron nitride (BN) fiber coatings in SiC/SiC composites was a breakthrough in the 1990s that carried into commercial products [2]. BN can self-heal (to some extent, it can crack but still provides a lubricious layer) and, critically, it’s resistant to air oxidation up to moderate temperatures. However, even BN has limits – in wet high-temperature environments (like a turbine with traces of moisture) BN can oxidize to borates. Researchers at ORNL and elsewhere found ways to optimize the thickness and quality of BN coatings to maximize composite toughness while minimizing environmental attack [2]. By controlling the coating thickness at the nanoscale, they achieved a consistent pull-out behavior and long-term stability. Some advanced CMCs even use a dual-layer coating (e.g. BN with an outer thin SiC or other ceramic) to further protect the fiber. These refined interphases made CMCs far more durable. The proof was in testing: CMC specimens with optimized BN coatings showed five-fold life improvements in certain oxidizing conditions compared to earlier versions [2]. Without these durable fiber coatings, the CMCs in service today could not meet the required lifetimes.

3. Environmental Barrier Coatings (EBCs): One of the biggest hurdles for non-oxide CMCs in engines was the risk of oxidation and moisture attack on the SiC. While SiC naturally forms a protective SiO₂ scale in dry air (up to ~1,600 °C) [5], in the presence of high-temperature steam that protective glassy SiO₂ can be mobilized (forming Si(OH)₄ vapour), leading to “recession” of the material. This was the very issue that had stalled the French program decades ago. The solution, developed largely in the 2000s, was a multi-layer Environmental Barrier Coating on the CMC surface. EBCs are to CMCs what thermal barrier coatings are to metals – except their role is to seal the composite from oxygen and water vapor. NASA and DOE scientists (e.g. Allen Haynes at ORNL) formulated EBC systems based on rare-earth silicates, mullite, and other oxides that adhere to SiC [2]. A typical EBC might consist of a bond coat (silicon), an intermediate layer (mullite or BSAS – barium strontium aluminosilicate), and a topcoat of ytterbium or yttrium silicate. These coatings prevent water vapor from reaching the SiC, thus stopping the corrosive weight loss. By the 2010s, EBCs had been tested on engine parts with great success – for example, in tests at 2,550 °F with high-pressure steam, coated CMC specimens showed order-of-magnitude lifetime gains [2]. GE and other engine companies incorporated EBCs on all hot-section CMC components (one can often see a light yellow or greenish tinge on CMC parts – that’s the outer oxide coat) [3]. Without EBCs, CMCs would not survive the real combustion environment for long durations; with them, parts can reliably last thousands of cycles. This development overcame the very problem that doomed earlier attempts.

4. Manufacturing Process Scale-Up and Optimization: Initially, making CMC parts was slow and artisanal. For instance, CVI (Chemical Vapor Infiltration) produces excellent quality CMCs by diffusing a vapor (like methyltrichlorosilane for SiC) through a hot fiber preform to deposit matrix, but it literally could take months to fully densify a thick part [2]. This is fine for prototypes, but impractical for mass production. Significant innovations occurred in processing:

- GE and others honed a “Prepreg & Melt-Infiltration” (MI) process. In this method, SiC fibers are first formed into a tape or cloth pre-impregnated with a polymer or slurry. Layers are laid up to near net shape, then pyrolyzed to create a porous char, and finally infiltrated with molten silicon or silicon alloy which reacts to form SiC matrix (this is also called reaction bonding or liquid silicon infiltration) [2]. The MI process is far faster than pure CVI – in hours you can infiltrate a part. GE’s production uses a version of this: they weave fiber preforms, apply a slurry of SiC particulate and polymer, stack/braid into shape, pyrolyze, and then do a melt infiltration of Si to fill residual porosity. By the late 2010s, GE had this process refined to produce thousands of parts per year. They publicly stated capacity to make 36,000 CMC turbine shroud segments per year by 2020 using the melt-infiltration method [2]. Such scale would have been unthinkable in the 1990s.

- Automation and Yield Improvements: Hand-layup of composites is labor-intensive. The industry invested in automating steps like fiber preform fabrication (e.g. 3D weaving machines, braiding of complex shapes) and robotic slurry infiltration. In one advance, engineers developed an automated braiding technique to create a seamless ring of CMC for turbine shrouds, rather than bolting together segments of cloth – this improved part consistency and reduced cracking at joints. Also, non-destructive evaluation (NDE) techniques improved, allowing manufacturers to examine CMC parts for pores or flaws using ultrasound, X-ray CT, or thermal imaging [2]. This is vital for quality control when ramping up production. The use of digital process controls and modeling (sometimes termed the “digital twin” of manufacturing) helped optimize cycles – for example, adjusting the heat treatment schedule to get the right matrix density while minimizing part distortion. The result was a steady rise in yields and drop in unit cost through the 2010s.

- Cost Reduction: Initially, CMCs were astronomically expensive ($>10,000 per part in some cases). But as facilities like GE’s Asheville plant and Safran’s plants came online, economies of scale kicked in. One report indicated that by iterating design and process, GE cut the cost of a CMC shroud for LEAP by roughly 2/3 between 2013 and 2017 [[11]]. This was achieved through yield improvements, cycle time reduction (they cut takt time of certain steps from 20 minutes to 5 minutes by automation), and supply chain integration. The establishment of large fiber production (e.g. the joint venture NGS Advanced Fibers in Japan and a new GE/Safran fiber plant in Huntsville, Alabama) was a major factor. Fiber cost historically dominated CMC cost – by mass-producing fiber tows (and improving fiber yield per batch), fiber costs dropped significantly, making the overall composite more affordable [2]. The U.S. government even supported this via a Title III program to ensure domestic SiC fiber supply and drive cost down [11].

5. Design & Analysis Tools for CMCs: Along with physical advances, engineers developed the analytical tools to predict CMC behavior, which was essential for certification. CMCs are anisotropic and their properties change with temperature and fatigue – far more complex than metals. Through the 2000s, companies and research labs built computational models (finite element codes) that could account for fiber/matrix micro-mechanics, creep, and oxidation effects [4]. They also established empirical allowables and design data from a vast testing campaign: millions of hours of testing were amassed (for example, by 2019 GE had over 2 million cumulative hours of CMC engine experience including tests [2]). This data enabled robust life prediction models. Regulatory bodies became comfortable that the behavior of CMCs was understood well enough to certify for flight. In 2016, when the LEAP engine was certified with CMC shrouds, it was a huge milestone – it signified that analytical methods and inspections were in place to ensure safety on par with traditional materials.

All these advances combined to solve the once-daunting puzzle of making reliable CMC parts at commercial scale. By addressing material longevity (fiber & coatings), environmental stability (EBCs), manufacturability (fast processes, automation), and predictability (design models), the CMC community removed each major technical roadblock one by one. The “game-changer” reputation of CMCs thus rests not on a single invention, but on a stack of innovations that, taken together, transformed a laboratory curiosity into a production-ready technology.

Commercialization and Industry Adoption: From Demo to Mainstream

The leap from promising prototypes to industrial adoption is often the hardest part of a materials innovation journey. For CMCs, this leap spanned roughly two decades (early 1990s demos to mid-2010s commercial use) and required unprecedented commitment from industry players. Here we outline how CMCs transitioned into real products, focusing on major programs and the new supply chain that underpins them.

Aerospace Engines – The First Big Win: The vanguard of CMC adoption has undoubtedly been commercial aircraft engines, specifically the CFM LEAP turbofan. After years of R&D, GE and Safran (through CFM) decided to make a bold move: incorporate a CMC component into one of the highest-volume engine programs ever. They chose a relatively conservative application for the first part – the stationary turbine shroud segments that line the hottest portion of the high-pressure turbine [2]. Shrouds see extreme heat (they encircle the rotating blades just past the combustor) but are non-rotating and primarily experience thermal and modest mechanical loads. This plays to CMC’s strengths (thermal resistance) while avoiding its weaker area (lower purely mechanical strength vs metal under high centrifugal loads). Each LEAP engine has 18 CMC shroud pieces forming a ring. By using CMC, these shrouds require vastly less cooling air than metal shrouds did [2]. In engine tests, the CMC shroud allowed the turbine to run at ~2,400 °F and saved enough cooling flow to help achieve the fuel burn improvement targets [2]. LEAP entered airline service in 2016, and the results have been excellent – by 2021, CMC shrouds in service had accumulated over 10 million flight hours without issues [[12]] [[13]]. This track record in hundreds of engines proved to the industry that CMCs were ready.

Following the shrouds, combustor liners were the next target. The combustor liner faces direct flame (often > 1,300 °C gas) and thus is usually film-cooled even in advanced engines. CMC liners can potentially eliminate film cooling holes, which improves combustion efficiency and emissions. GE’s large GE9X engine (for the Boeing 777X, certified in 2020) contains two CMC combustor liner segments, along with CMC turbine shrouds and nozzles [11]. This engine has five CMC parts in total – making it the record-holder for ceramic content in a commercial engine. With the GE9X, GE even used CMC in some high-pressure turbine nozzles (vanes), which broadened the usage beyond just shrouds.

Meanwhile, military engines also started adopting CMCs beyond just exhaust parts. GE’s prototype ADVENT adaptive cycle engine (a next-gen military jet engine demonstrator) ran tests with CMC parts deeper in the hot section, including some rotating parts. In 2019, GE reported the first successful tests of rotating CMC turbine blades in an F414 engine core – a landmark moment [6] [[14]]. The CMC blades endured 500+ cycles at high speed and temperature, demonstrating durability [6]. While not yet fielded in an operational engine, this indicated that even the most demanding components (rotors) could one day be ceramic composites. The U.S. Navy and Air Force are keenly interested in CMCs for future adaptive-cycle engines and for extending the life of existing engines. It’s telling that GE’s first use of CMC was actually in the F136 engine (a prototype for the F-35) back around 2005 [3], where they used CMC shrouds. That engine program was canceled, but it gave GE confidence to later roll those learnings into the LEAP and GE9X. Now, Pratt & Whitney (the other major U.S. engine maker) is also working on CMCs, reportedly testing them in advanced versions of their F135 fighter engine and in technology demonstrators for sixth-gen jets. By the mid-2020s, it’s expected that any new high-performance engine will incorporate CMCs in some form, due to the clear performance advantages.

Hypersonics and Space: In the realm of hypersonic vehicles and spacecraft, CMCs are transitioning from experimental to essential. Space agencies and defense contractors have put CMC nosetips, leading edges, and control surfaces on test vehicles to enable reuse or higher speed trajectories. For example, NASA’s X-37B spaceplane (unmanned mini-shuttle) reportedly uses advanced composite thermal protection (possibly CMC tiles or flaps) to survive repeated re-entries. The European Space Agency in its 1990s Hermes and 2000s EXPERT/IXV programs qualified C/SiC composite leading edges and control flaps for re-entry conditions ~1,600 °C [5]. Although those particular spaceplane programs didn’t go operational, the technology was handed off to later projects. Today companies like Hypersonix (Australia) and SpaceX are investigating CMCs for scramjet combustion chambers and control fins – Hypersonix fabricated a C/SiC scramjet chamber that can handle 1,400 °C for their hypersonic drone, as a step toward full CMC engines [6]. And in Europe, aerospace firms have developed ceramic composite clamping and fastening systems (bolts, nuts) that hold up in extreme heat, enabling all-CMC assemblies for space vehicles [5]. In summary, while not yet as visible as in jet engines, the adoption of CMCs in hypersonic and space systems is accelerating, driven by the simple fact that they are often the only option for the performance required (short of exotic one-shot ablatives).

Energy and Industrial Applications: The commercial power generation sector has been slower, but it’s starting to follow. Solar Turbines, under DOE programs, ran a field test with a CMC combustor liner that achieved ultra-low emissions and high firing temperature [11]. Although not yet a standard product, the success led to continued development for stationary turbines. One factor is that power turbines value longevity; materials may need a 30,000+ hour life. By accumulating 40,000 hours of data from industrial turbine tests on CMCs [11], GE and others built confidence that long-term durability is feasible. In 2019, a DOE program called HyTEC (High Temperature Engine Components) was initiated, aimed at introducing CMCs into next-gen power turbines and perhaps even into nuclear reactors (as structural components or fuel cladding). There is active research on SiC/SiC CMC cladding for nuclear fuel in light water reactors, as part of “accident tolerant fuel” concepts – the idea is that SiC cladding could better withstand beyond-design-basis accidents (as evidenced in lab tests, it has very low oxidation in steam up to high temperatures). Several test irradiations of CMC cladding have been done with promising results, but regulatory adoption will be slow.

The CMCs supply chain had to be built almost from scratch during the 2010s to support these adoptions. Key elements include:

- Fiber Production: Initially, virtually all SiC fiber came from Japan (Nippon Carbon’s plant). To ensure supply, GE, Safran, and Nippon Carbon formed a JV called NGS Advanced Fibers in Japan to scale up output of Hi-Nicalon S and Sylramic fibers [11]. Then GE invested ~$100 million in a new U.S. fiber plant in Huntsville, Alabama, which opened in 2018–2019 [11]. This Huntsville facility is the first high-volume SiC fiber plant in the West, aimed at producing many tons of fiber annually. Having multiple fiber sources is crucial to avoid bottlenecks (today, NGS in Japan and Huntsville in US are two main sources; Ube Industries in Japan is another fiber supplier with their “Tyranno” fiber, and China is reportedly developing its own SiC fibers for domestic use).

- Matrix Precursor and Preform Facilities: GE established a full CMC manufacturing campus in Asheville, North Carolina (opened 2014) [11]. This factory takes in fibers (from Japan or Alabama), weaves or lays them up with a proprietary slurry into green parts, then performs the melt infiltration and machining to output finished CMC components. Asheville started with shrouds for LEAP and expanded to combustor liners for GE9X. By 2018, GE celebrated the shipment of its 100,000th CMC turbine shroud from this facility – a remarkable scaling milestone [[15]]. Other players: Safran has a plant in Bordeaux, France for CMC parts (stemming from the legacy of SEP); COI Ceramics in the US (a consortium including Northrop Grumman) produces CMC parts primarily for defense; in Europe, Herakles (part of Safran) makes C/C and C/SiC for space and military.

- Coating and Finishing: CMC parts typically go to a separate station for EBC application and final machining. GE forged a joint venture “Advanced Ceramic Coatings” with Turbocoating of Italy, and built a coating plant in Duncan, SC [2]. There, CMC components receive their BN interphase (if not applied earlier) and the outer EBC layers, using processes like chemical vapor deposition or plasma spraying. Precision grinding and drilling (for any holes to mount parts) are also done, as CMCs require diamond tooling to machine. Over the 2010s, these specialized steps have become streamlined. For example, in aerospace manufacturing news, it’s noted that by 2020, GE could produce a finished CMC shroud every 15 minutes or so across their flow line – an astonishing pace compared to the artisanal lab procedures of earlier days [2].

- Inspection and Testing: Both optical/ultrasonic inspection and engine testing capacity had to grow. GE’s test cell in Peebles, Ohio, was heavily utilized to certify CMC parts – e.g. they ran a GEnx engine with CMCs for thousands of cycles to validate the GE9X design [3]. Also, firms like UTC (now Raytheon Technologies) and NASA set up dedicated test rigs for CMC evaluation under combined thermal/mechanical loads to generate data for certification. It became routine to do “block tests” where an engine is pushed beyond normal conditions (say, over-temperature) to see how the CMCs hold up – and they have generally passed with flying colors, sometimes outlasting metal counterparts.

All these pieces – fiber plants, part fabrication plants, coating facilities – represent a new supply chain for a new class of materials. Building it was expensive. GE alone invested over $1.5 billion in CMC development and production capacity by the late 2010s [2]. This is a massive bet, reflecting a long-term view that CMCs will be core to many future products. In parallel, government programs provided support (e.g. U.S. DoD and DOE funds for pilot production, EU funds for advanced material SMEs, etc.).

The payoff is that today, an aerospace customer can actually order CMC components at production scale – something that was impossible 15 years ago. As a result, we see adoption spreading: Boeing and Airbus are open to CMCs in auxiliary power units and environmental control systems; automakers eye CMC exhaust components for high-end engines (because they could eliminate heavy heat shields); and industrial manufacturers consider CMC furnace fixtures or heat exchangers for aggressive environments.

One interesting aspect of commercialization is how competition accelerated once CMCs proved themselves. For instance, after GE’s success, Rolls-Royce partnered with CoorsTek to develop oxide CMCs for engine hot ducts (they avoided the U.S.-patent-heavy SiC/SiC route initially). Several Japanese conglomerates (like IHI, Mitsubishi) have their own CMC initiatives, especially for military jet engine components in Japan’s next-gen fighter. In China, institutions are pouring resources into CMC research for engines and hypersonics, as evidenced by a surge in Chinese journal publications on SiC fibers and CMC coatings in the last few years. So the supply chain is likely to globalize and diversify, which should further drive down cost and increase availability.

In summary, by the mid-2020s CMC commercialization has achieved self-sustaining momentum. A user in industry can specify a CMC solution and reasonably expect it to be delivered, thanks to the mature supply ecosystem established by the pioneering programs (LEAP, GE9X, etc.). The journey from isolated lab samples to 100,000+ production parts is a testament to coordinated effort across science, engineering, and business domains. And while aerospace engines led the way, the door is now open for many other sectors to piggyback on that success and incorporate CMCs for their high-temperature needs.

Competitive Landscape: How CMCs Outperformed the Alternatives

It’s instructive to examine what other technologies CMCs were up against, and why CMCs ultimately “won” in their niche. Prior to CMCs’ rise, engineers had a toolkit of stop-gap measures and alternative materials for high-temperature, high-stress applications – none of them ideal. The table below summarizes key competitors to CMCs and their limitations:

Table 1. High-Temperature Material Options Before CMCs

| Category | Examples | Key Weaknesses |

| Nickel Superalloys (cooled) | Inconel™, René alloys in turbine blades/shrouds | Heavy (density ~8.5 g/cc); require complex internal cooling and thermal barrier coatings to survive beyond ~920 °C [4]. Cooling air use reduces engine efficiency. Ultimately limited by melt point (~1,350 °C) and creep. |

| Monolithic Ceramics | SiC, Al₂O₃, ZrO₂ parts (unreinforced) | Extremely brittle – low fracture toughness means catastrophic failure from minor cracks or impact [5]. Cannot sustain tensile stress or thermal shock. Difficult to design reliable components, and typically require over-design (thickness, safety factors) that add weight. |

| Carbon–Carbon Composites | Carbon fiber / carbon matrix (C/C), e.g. Space Shuttle nose cap, aircraft brake disks | Good strength up to 3,000 °C in vacuum, but in air oxidizes above ~500 °C (carbon burns to CO/CO₂) [7] unless protected. Thus either used in oxygen-starved environments or with coatings (which can crack). Used as ablatives or in short-life applications. Not suitable for long-term use in oxidative environments without continuous protection. |

| Ablative Ceramics & Coatings | Carbon-phenolic heat shields; sacrificial ceramic coatings | Designed to erode/ablate to carry away heat (e.g. rocket nozzles, reentry shields). One-time use: material chars or vaporizes [6]. Requires refurbishment or replacement each mission. Adds weight and thickness (ablative layers are not load-bearing). For reusable systems, ablatives incur high maintenance and turnaround time. |

| Advanced Metal Alloys & TBCs | E.g. single-crystal superalloys with YSZ thermal barrier | Incremental improvement only. Complex fabrication (single-crystal) and cooling still needed. Thermal barrier coatings can spall; only protect for maybe 100–300 °C increase [3]. Metals also have high thermal expansion, causing thermal stress issues. Ultimately cannot reach ceramic-level temperatures without active cooling. |

| Refractory Metals & Intermetallics | Tungsten, Tantalum alloys; Mo–Si–B alloys; TiAl intermetallics | Refractory metals: very high melting points but extremely dense (W, Ta >16 g/cc) – weight prohibitive; also often brittle at service temps. Prone to oxidation (need coatings). Intermetallics (like Ti aluminides): lighter but limited to mid-range temperatures (~750 °C) – not hot enough for turbine prime reliance. |

No single one of these alternatives provided the combination that CMCs offer: **high heat tolerance (1200–1500 °C), structural load capability, oxidation resistance (with coatings), and lightweight toughness. Nickel alloys were tough but too low-temp; monolithic ceramics had temp but not toughness; C/C had temp and low weight but failed in air; coatings/ablatives were only temporary shields.

When CMCs arrived at sufficient maturity, they effectively leapfrogged these alternatives in certain applications:

- In turbine hot sections, CMCs didn’t just add a few degrees – they raised allowable gas temperatures by a few hundred degrees without cooling air [2], something no metal+coating solution could do. This was decisive for efficiency gains.

- In weight-critical systems (aerospace, missiles), saving 66% of the weight of a hot part was a revolutionary improvement [1]. It’s worth noting: even if metals could handle the heat with heavy cooling, they’d still penalize the system by their mass. CMCs dramatically improved the thrust-to-weight or power-to-weight ratios.

- Against carbon-carbon in reentry or hypersonics, CMCs (especially SiC/SiC or C/SiC with proper coatings) offered reusability. Instead of burning off and requiring replacement, a CMC leading edge or engine component can be used repeatedly (Hypersonix explicitly noted that CMCs enable reusability whereas ablatives do not [6]). For the emerging space economy and high-cadence launch plans, that’s a game-changer.

- Oxide CMCs, while lower temperature, beat out high-temperature metals in certain corrosive environments (e.g. chemical processing or gasifier linings) because they resist oxidation and corrosion inherently [5]. For example, a Ni alloy might soften or corrode at 1000 °C in a furnace, whereas an oxide CMC could handle it for much longer. Thus CMCs found some niches in industrial heating where lifespan trumps initial cost.

One could ask, why not just stick with improving metals via coatings or using more exotic metal combos? The answer is partly physics and partly practicality. Physics-wise, metals have fundamental limits – their strength falls off near their melting point and they have high thermal conductivity which makes cooling them paradoxically harder (heat conducts to where you don’t want it). Ceramics have stable strength at high temps and lower thermal conductivity, meaning a CMC part can maintain a hotter surface while the back face stays cooler. In a sense, CMCs created a temperature gradient management advantage beyond what even the best thermal barrier on metal could do [4].

Practically, by the 2010s, it was evident that metals were on a curve of diminishing returns – each incremental improvement cost more and yielded less. The big engine makers had already squeezed a lot from single-crystal casting, alloy tweaks, cooling airflow optimization, etc. CMCs represented a step-change – a new curve to jump to. Competitive analysis showed that if one company deployed CMCs successfully and others stuck to metals, the CMC adopter would gain a significant performance edge (better fuel burn, etc.). Indeed, after GE’s leap with CMCs, competitors had to respond. Rolls-Royce, for example, announced it was working on its own composite turbine components to not be left behind. Safran, partnering with GE, ensured access to the tech. Pratt & Whitney initially touted its alloys plus clever cooling approach (for its GTF engine), but industry observers noted that Pratt could eventually face a thermal limit, whereas CFM with CMCs had more headroom for future improvements [3].

Another alternative to CMCs that sometimes comes up is ceramic coatings on ceramics – for example, could one just use a monolithic ceramic with a fiber or metal backing? Some rocket engines use “tiled” approaches (like coating a copper liner with a ceramic layer). However, those are very specific and don’t carry structural loads well. CMCs won because they themselves are structural materials. You can bolt a CMC part in place of a metal one (with some design tweaks) and it will carry load and function, not just insulate. This made adoption somewhat more straightforward – one doesn’t have to redesign the entire system concept.

In summary, CMCs succeeded in their competitive landscape by delivering a unique combo of properties that no other material or combination could match. They essentially neutralized the weaknesses of monolithic ceramics (by adding toughness) while exploiting the advantages of ceramics over metals. The alternatives either failed in one critical aspect (temperature, weight, or durability) or were only partial measures.

The case of ablatives vs CMC for hypersonics nicely illustrates the trade: an ablative TPS can protect once, but a CMC TPS can protect and be reused, which for future systems is a decisive advantage [6]. Similarly, a cooled metal turbine can survive heat but at the cost of efficiency, whereas a CMC turbine part can survive and improve efficiency.

It’s worth noting that CMCs haven’t completely displaced all these alternatives; rather, they carved out the high end of the market. Metals are still used in slightly cooler sections with well-established methods, and ablatives are still cheapest for one-off reentry capsules. But where performance is king – advanced jet engines, stealthier and faster missiles, re-usable spacecraft – CMCs have become the go-to solution, essentially winning by default because nothing else can meet the spec.

Why It Succeeded: Keys to CMCs’ Breakthrough

Looking back at the CMC innovation journey, we can identify several critical factors that signaled and ensured its ultimate success – both technically and commercially:

Clear and Pressing Market Need: By the early 21st century, the need for a material like CMC had become stark. Jet engines needed to run hotter for efficiency and emissions reasons; no other way existed to get, say, a 15% efficiency jump in one generation [2]. Hypersonic vehicles and reusable spacecraft flatly required materials beyond metals [7]. This strong market pull meant that if CMCs could be made to work, customers were ready to adopt them despite higher costs. It’s a classic case of demand-driven innovation – the pain point (fuel cost, performance, etc.) was so acute that it justified the risk of trying a new material. In the LEAP engine example, airlines were willing to bet on unproven CMC parts because the fuel savings (~15%) was enormously valuable over the life of the engine [2]. Such willingness is a harbinger of commercial success if the technology can deliver – and it did.

Decades of Scientific Foundation (Dormant Tech Readiness): CMCs might have seemed to burst on the scene in 2016 with the LEAP engine, but in truth they rode on 30+ years of foundational research. By the time of commercialization, the science was solid and much of the risk had been retired in the lab or in demos. All those “dormant” projects – NASA’s fiber coatings, DOE’s CFCC tests, the French and Dornier trials – provided a treasure trove of data and lessons [2] [4]. In other words, when the green light for commercialization came, it wasn’t starting from scratch; it was scaling something whose core concepts were already proven. This base of R&D meant the technical feasibility was high. An observer in 2005 could see that continuous SiC fibers existed, that lab CMCs had survived thousands of hours in tests, that military jets had flown with CMC bits – so the science wasn’t speculative, it just needed engineering integration. This technology readiness (albeit mostly on TRL 4–5 level) was a positive indicator that the leap to TRL 7–9 (operational use) could be made within a decade, which indeed happened.

Champions and Commitment – The Role of Industry Leaders: The importance of a champion organization cannot be overstated. In this story, GE Aviation played that role. GE bet big on CMCs, investing on the order of $1+ billion of its own funds to build facilities and acquire materials companies [2]. They had a visionary materials scientist (Krishan Luthra at GE Global Research) who evangelized CMCs internally since the late 1980s [1], ensuring that when the time came, GE was prepared to execute. GE’s commitment was apparent: they fast-tracked development by leveraging their interdisciplinary strengths (materials + design + manufacturing), and even pivoted across divisions (when GE Power’s turbine group wasn’t ready to adopt CMCs, GE Aviation picked it up) [1]. This reflects a principle: breakthrough materials often need a champion with deep pockets and patience. Corning did it for Gorilla Glass; GE did it for CMCs. Other companies (like Safran, Rolls-Royce, and smaller players) joined in, but GE’s early leadership set a pace. An industry observer could see by ~2010 that GE was building factories in anticipation of success [1] – a strong sign that this was not a science project but a serious commercialization effort. When such a major pulls in this direction, suppliers, regulators, and customers pay attention and align.

Successful Demonstrations & Risk Reduction: There were key inflection points where technical validation tipped opinions in favor of CMCs. For example, GE’s full engine test of rotating CMC blades in 2015 (in an F414) wowed skeptics – spinning parts endure the worst conditions, and CMC blades surviving 500 cycles gave credence that the material was as good as advertised [6]. Similarly, when the LEAP entered service and accumulated thousands of flight hours with no CMC issues, it quelled remaining reliability fears. Each of these milestones – hours accumulated, cycles without crack, etc. – served as proof points. Years earlier, at the concept stage, one might have doubted if ceramics could hold up to bird strikes or vibration. But CMC manufacturers deliberately tested such scenarios (e.g. ingesting objects into engines with CMC liners to ensure they didn’t shatter – they didn’t; CMCs tend to crack slowly and remain contained due to fiber bridging). By meeting certification requirements and matching metal parts in rigorous testing, CMCs proved themselves. In innovation management terms, they had crossed the “valley of death” between lab success and field confidence. Once airlines and militaries saw that the material had been proven in use (even if only for a year or two), the floodgates for orders opened.

Unique Performance that Mapped to Value: We should note the alignment of CMCs’ capabilities with key value propositions. CMCs weren’t just a little better; they were an order-of-magnitude improvement in some metrics. For example, CMC shrouds cut required cooling air by ~20% and allowed higher temperature – those are big numbers that translate to fuel savings [2]. In markets like commercial aviation, a 1% fuel burn reduction is worth billions in fuel over a fleet’s life. LEAP offered 15% improvement partly enabled by CMCs – that’s enormous. Thus the ROI could be clearly calculated and was very attractive, justifying the higher initial cost of CMC parts. Contrast this with many new materials that only offer marginal benefit which might not justify re-tooling a supply chain. CMCs avoided that trap by hitting the sweet spot: something no other material could do (run so hot, so light, for so long).

Strategic Patience and Vertical Integration: Another less obvious but crucial factor: the main players vertically integrated the supply chain (fibers, matrix, coatings) and were willing to absorb initial cost hits. GE, for instance, bought a CMC facility in Delaware in 2002 and used it as a “lean lab” for low-rate production, essentially incubating the manufacturing know-how in-house [2]. They also formed JVs for fiber and coatings, rather than relying on a third-party to magically deliver those. This meant they controlled their destiny and could iterate quickly between design and manufacturing. We saw this in Gorilla Glass too (Corning leveraging its LCD glass production lines to mass-produce Gorilla). In CMCs, GE’s vertical integration ensured that scale-up and cost reduction happened on their schedule and met their engine timelines. An outside observer around 2014 could note GE’s moves – acquiring supply chain elements, ramping fiber plants – and infer that they had solved enough of the technical issues and were now in the execution phase. This was a strong indicator that the CMC effort wasn’t going to fizzle as so many materials developments do in pilot stage.

Regulatory and Ecosystem Support: The final success factor is a bit broader: the ecosystem (government and industry) supported the transition. FAA and EASA (aviation regulators) were engaged early to certify CMCs; military program offices funded risk-reduction experiments (like the AFRL paying for that rotating blade test). DOE kept funding advanced CMC coatings and modeling through the 2010s to address remaining questions. Even international collaboration played a role: for instance, the Japanese NGS SiC fiber JV showed that multiple companies and countries cooperated to ensure supply, sharing both risk and reward [11]. This collective support reduced barriers. A material innovation can fail if, say, regulation doesn’t know how to approve it – but in CMCs’ case, the groundwork (standards for testing, etc.) was laid such that by the time of deployment, it wasn’t a regulatory nightmare. Indeed, Gorilla Glass and CMCs share that trait: by launch, both had enough demonstration that customers and regulators were comfortable.

In summary, CMCs succeeded due to a convergence of technology readiness and market necessity, championed by big players with a long-term vision, and punctuated by convincing demonstrations that erased doubt. The timeline had many moments where it could have failed (had, say, LEAP’s CMC shroud cracked in service frequently, it would be a different story), but meticulous preparation and incremental proving ensured that by the time the spotlight was on, CMCs delivered.

One might say CMCs’ success was a textbook case of the right innovation at the right time: the need was there, the science was ready, and the execution was bold.

Lessons for Innovators in Materials Science

The saga of ceramic matrix composites offers rich insights into how breakthrough materials come to fruition. Here are some key lessons gleaned from this journey:

1. Big Problems Need Big Solutions (and Patience): CMCs addressed a massive pain point – the heat barrier in engines – which gave them a clear value proposition. However, it took decades for the technology to mature enough to solve that problem. Innovators should recognize that materials breakthroughs often require a long gestation. Early research in the 1970s and 80s didn’t find immediate use, but when the world caught up to need that capability, the prepared technology bloomed. Lesson: Keep pushing the frontiers of materials science even if the market isn’t ready yet – one day, an “unsolvable” problem will emerge that your dormant innovation can solve.

2. Interdisciplinary Integration is Crucial: The success of CMCs hinged on a combination of advanced chemistry (fibers, coatings), mechanical engineering (designing composite parts), and manufacturing science (scaling processes). GE’s team had ceramicists, mechanical engineers, and production experts working hand-in-hand [1]. This interdisciplinary approach meant problems were solved holistically (e.g., adjusting part geometry to ease manufacturing, or tailoring fiber coatings to improve design margins). Lesson: Materials innovation is not done in a vacuum – collaboration across disciplines (and between R&D and manufacturing) is essential to move from lab to product.

3. Government and Public-Private Partnership Can De-risk Innovation: The CMC story would likely not have succeeded without early funding and support from organizations like DOE, NASA, and DoD. Those CFCC programs and engine demos in the 90s provided critical data and kept the field alive until industry was ready [2]. Public funding essentially carried the technology through the “valley of death” for many years, advancing it to a point where commercial entities could take over. Lesson: For high-risk, high-reward materials, leveraging government programs or consortia can sustain development during periods when direct commercial investment is hard to justify [2]. It also helps set standardized testing and share knowledge pre-competition.

4. A Champion with Vision and Resources Makes a Difference: As highlighted, GE’s championing was pivotal. Not every new material is fortunate to have a major corporation betting on it. But when it happens, it can change the game. These champions often have what one might call “organizational memory” of past R&D (GE had been working on CMCs internally for decades, just like Corning had the Chemcor glass in its vault) [1]. Lesson: If you are an innovator inside a company, building that long-term case and keeping the flame alive (as Luthra did at GE) can set the stage for when market timing aligns. If you’re outside, finding a partner or champion firm who believes in the vision increases the odds of success exponentially.

5. Timing Is Everything: In the 1990s, one could argue CMCs were a solution looking for a problem – the materials worked, but the market didn’t urgently need them. By the 2010s, the timing was finally right. Smart innovators assess the market window: Corning realized in 2005 that smartphones were the window for Gorilla Glass; GE realized in mid-2000s that the next engine cycle was the window for CMCs. Lesson: Align your innovation efforts with emerging market inflection points. Sometimes that means patiently waiting or doing small-scale pilots until the demand curve steepens. Launching too early can lead to failure out of lack of adoption; too late, and a competitor might steal the march.

6. Don’t Compete Head-On with Incumbents – Leapfrog Instead: CMCs didn’t aim to replace metal in all applications – they targeted the regime where metals could not go. By focusing on that extreme niche (ultra-hot sections), they avoided direct competition with cheaper metals in easier roles. This allowed CMCs to prove their value where nothing else could do the job. Lesson: For new materials, find the beachhead application where your material is not just a little better, but the only viable solution or a drastically superior one. That way, you’re not fighting entrenched materials on their turf, but creating a new turf. Once established in the high-end niche, you can expand scope (as CMCs now are expanding to more parts of the engine).

7. Overcoming Skepticism Requires Demonstration and Data: Early in the CMC journey, many engineers scoffed at the idea of ceramics in engines (“When pigs fly” was the joke [1]). Convincing the skeptics took real-world tests that shattered preconceived notions – like running an engine and finding the metal blades wore against the CMC shroud, but the shroud was fine. After that, the mechanical engineers “were no longer fearful of the material” [1]. Lesson: Especially for materials with an iffy reputation, seeing is believing. Invest in pilot implementations, demos, and rigorous testing early on. No amount of papers or promises equal the persuasive power of “it already ran in a real system under real conditions” [1].

8. Iterate on Manufacturing from Day One: GE didn’t wait to solve all manufacturing issues after the material was perfect; they concurrently developed the melt infiltration process and scaled it in parallel to materials development. This “process innovation” aspect was as crucial as the material innovation. Lesson: Don’t separate material discovery from manufacturability. Develop the production methods alongside the material, or you might end up with a lab wonder that can’t be economically made. Involvement of manufacturing engineers early (as GE did with their Lean Lab approach) ensures that scaling challenges are addressed incrementally rather than as a massive hurdle at the end.

9. Keep Pushing the Next Horizon: Now that CMCs have succeeded, the story isn’t over. There are already efforts to go to “Ultra-High-Temperature CMCs” (UHTCMCs) using additives like refractory carbides for hypersonic needs beyond 1,500 °C [[16]]. The materials community is constantly asking “what next?” – perhaps composites with even higher use temps, or ones that self-heal oxidation, etc. The principle is that innovation is a continuum. Each success (like CMCs at 1,300 °C) becomes the stepping stone for the next goal (CMC at 1,500+ °C). Lesson: Successful innovation doesn’t stop at one breakthrough. Teams should capture the momentum and knowledge and set sights on the next generation. That’s how you maintain leadership and also how you future-proof the innovation against potential new challengers (e.g., maybe in 20 years some high entropy alloy or a metamaterial comes along – CMC proponents will want to have evolved further by then).

10. Materials Innovation is a Team Sport: Finally, the CMC journey underscores that no single person or even single organization could do it all. It required a global effort – Japanese fiber, American engines, European ceramic research, etc., all contributing pieces. It also required buy-in from material scientists through to design engineers and even marketing folks (to convince customers to accept a new material, which can be a selling point or a scare point). Lesson: Build a coalition around a material innovation. Engage academia (for fresh ideas and fundamentals), industry (for application and funding), government (for initial support and standards), and even end-users (to pilot and give feedback). This broad base creates a robust environment for the material to mature and be adopted.

In conclusion, the rise of ceramic matrix composites from a lab curiosity to a linchpin of modern aerospace is a study in perseverance, timing, and the synergy between science push and market pull. It teaches us that solving the “unsolvable” often demands revisiting shelved ideas, investing deeply in multi-front innovation (material + process + design), and waiting for (or catalyzing) the right moment when the world truly needs what you have developed. It’s a dramatic example of how advanced materials can redefine what engineered systems are capable of, and a reminder that the materials of tomorrow’s world are being dreamed up in labs today, awaiting their turn to take flight.

References:

[1] GE Research, “When Pigs Fly: Behind the Breakthrough of Ceramic Matrix Composites,” GE Aerospace News, Aug. 2019. https://www.geaerospace.com/news/articles/manufacturing-technology/when-pigs-fly-behind-breakthrough-ceramic-matrix-composites#:~:text=looks%20forward%2C%20the%20impact%20of,higher%20than%20most%20advanced%20metals

[2] ORNL, “Ceramic matrix composites take flight in LEAP jet engine,” Oak Ridge National Lab News, Jan. 2017. https://www.ornl.gov/news/ceramic-matrix-composites-take-flight-leap-jet-engine#:~:text=January%203%2C%202017%20%E2%80%93%20Ceramic,completely%20and%20emitting%20fewer%20pollutants

[3] GE Reports, “Space Age Ceramics Are Aviation’s New Cup of Tea,” Jul. 2016. https://www.ge.com/news/reports/space-age-cmcs-aviations-new-cup-of-tea#:~:text=GE%20scientists%20have%20been%20working,power%20and%20burn%20less%20fuel

[4] National Research Council, Ceramic Fibers and Coatings: Advanced Materials for the 21st Century, 1998, Ch.2. https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/6042/chapter/4

[5] Wikipedia, “Ceramic matrix composite – Introduction.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceramic_matrix_composite#:~:text=The%20motivation%20to%20develop%20CMCs,very%20low%2C%20as%20in%20glass

[6] Hypersonix Launch Systems, “A new era for ceramic matrix composites,” Oct. 2023. https://www.hypersonix.com/resources/news/a-new-era-for-ceramic-matrix-composites#:~:text=small%20satellites%20to%20orbit,Hypersonix%20recently%20received%20a%20C%2FSiC

[7] Science Learning Hub, “Materials for hypersonic vehicles,” 2011. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/388-materials-for-hypersonic-vehicles

[8] M. Takeda, “Progress of silicon carbide fibers and their application to ceramic matrix composites,” ECI ACMC Proceedings, 2017. https://dc.engconfintl.org/acmc/53/#:~:text=Silicon%20carbide%20fibers%20have%20high,TM%7D%2C%20in%201983

[9] G. Karadimas, K. Salonitis „Ceramic Matrix Composites for Aero Engine Applications—A Review“ Appl. Sci. 2023, 13(5), 3017; https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053017

[10] R. Yancey „Meeting the High-Temperature Material Challenges of Hypersonic Flight Systems“, https://www.hexcel.com/Resources/hypersonics#:~:text=Meeting%20the%20High,key%20technology%20for%20hypersonic

[11] „Ceramic Matrix Composites Taking Flight at GE Aviation“https://de.scribd.com/document/415001473/Ceramic-Matrix-Composites-Taking-Flight-at-GE-Aviation#:~:text=Cost%20Out%20%E2%80%93%20LEAP

[12] C. Massie, GE Aerospace „Meet the Super Material Helping GE’s Adaptive Cycle Engine Deliver Transformational Performance“ March 30, 2022 https://www.geaerospace.com/news/articles/manufacturing-product-technology/meet-super-material-helping-ges-adaptive-cycle-engine#:~:text=Meet%20the%20Super%20Material%20Helping,and%20more%20than%20100%2C000

[13] M. Tyrrell „GE hopes to upgrade F-35 and power NGAD using this super material“,11th Apr 2022 https://www.aero-mag.com/ge-aviation-xa100-ngad-11042022#:~:text=mag,and%20more%20than%20100%2C000

[14] B. A. Bednarcyk, S. K. Mital, E. J. Pineda, S. M. Arnold „Multiscale Modeling of Ceramic Matrix Composites“, 56th AIAA/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference 5-9 January 2015 https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/6.2015-1191