Introduction: A Quiet Revolution in Concrete Technology

Today’s skyscrapers, bridges, and sustainable buildings owe much of their performance to a once-obscure class of chemicals known as polycarboxylate ether (PCE) superplasticizers. These advanced admixtures, introduced in the 1980s, enable concrete to flow easily with far less water, yet harden to higher strength and durability than ever before [[1]] [[2]]. PCE superplasticizers have become the cornerstone of high-performance concrete, allowing engineers to pour self-leveling floors, pump concrete to record heights, and incorporate environmentally friendly mix designs. Since their invention in 1981, PCEs have grown from a lab curiosity into a multi-billion dollar global technology – a major breakthrough and milestone in modern concrete construction [2]. What follows is the story of how this innovation emerged, overcame technical and market hurdles, and fundamentally changed the world of concrete.

The Pain Point: When Traditional Admixtures Hit Their Limits

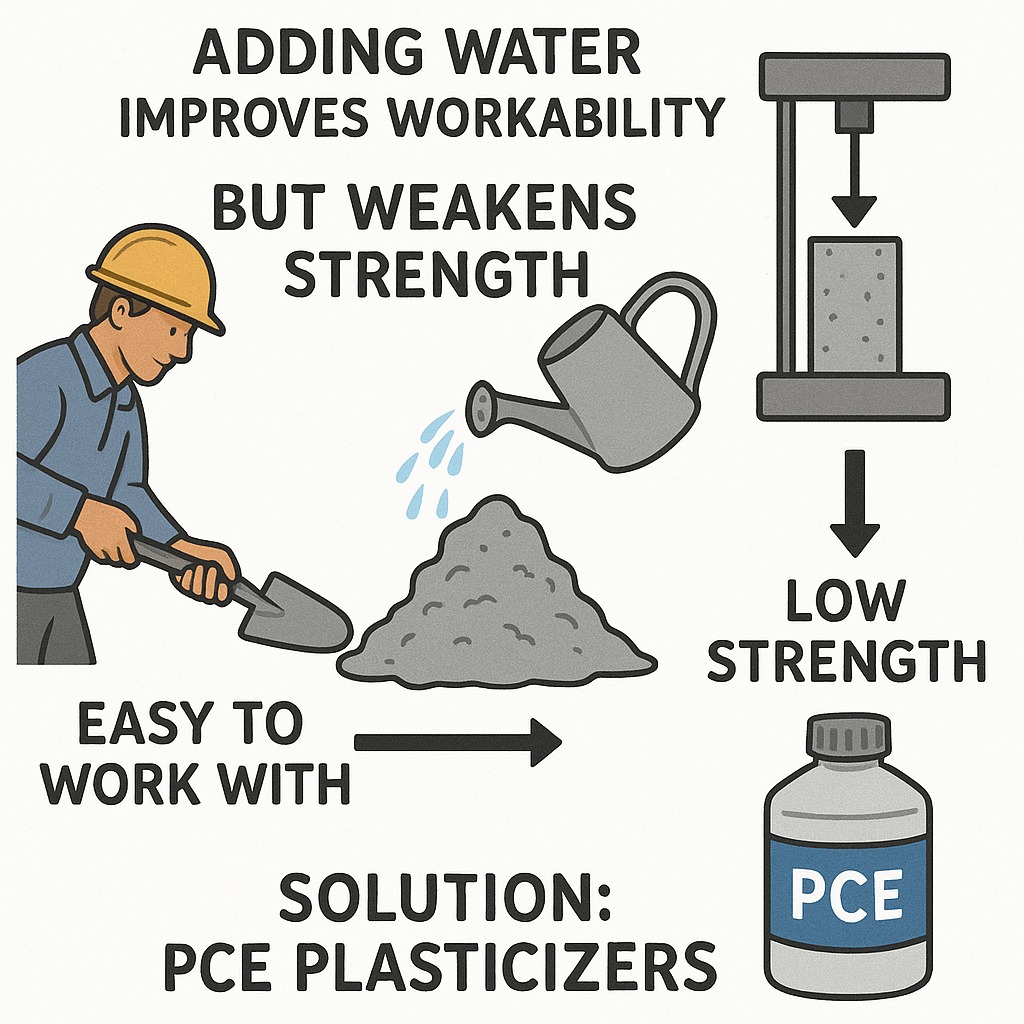

Through the mid-20th century, builders struggled with a classic concrete trade-off: adding water made concrete easier to work with, but drastically weakened the final strength. Early additives offered only partial relief. As far back as the 1930s, byproduct lignosulfonates from paper mills were used as plasticizers to improve concrete workability, but they could only do so much – water reduction was modest and strength gains minimal [1]. In the 1960s, the first high-range water reducers (so-called superplasticizers) were introduced: sulfonated melamine-formaldehyde and naphthalene-formaldehyde condensates [1]. These second-generation admixtures allowed greater water reduction and slump improvement, helping launch early high-strength concrete in the 1970s. However, they came with serious limitations. Their dispersing action, based purely on electrostatic repulsion, was short-lived – concrete could lose workability within minutes in hot weather. They were sensitive to cement chemistry and other additives, often causing unpredictable set behavior at higher doses [1]. Moreover, being formaldehyde-based products, they raised environmental and health concerns (releasing odors like ammonia or formaldehyde). By the late 1970s, the construction industry’s needs had outgrown the capabilities of these admixtures. Projects were demanding ever-higher strength and flow, but existing plasticizers couldn’t hit the required performance sweet spot. Contractors in hot climates saw concrete slump vanish before placement; engineers pushing for 8000+ psi (≥55 MPa) concrete found traditional superplasticizers either couldn’t achieve the needed water reduction or caused side effects like flash setting or excessive retardation. The stage was set for a new solution.

PCE superplasticizers as a solution for classic concrete trade-off

A Nation in Need: Japan’s Concrete Crisis of the 1970s

The turning point came in Japan. In the late 1970s, Japan was experiencing a construction boom – rapidly building highways, skyscrapers, and infrastructure – but the quality of concrete was under threat. The country faced a shortage of good aggregate, declining aggregate quality, and pervasive durability issues like alkali-aggregate reaction (AAR) [2]. These problems meant that achieving strong, durable concrete required using less water and more cement – which in turn made the concrete mix extremely stiff and difficult to work with. The conventional superplasticizers (naphthalene and melamine types) were not solving the issue; at high dosage they often failed to maintain workability or introduced set irregularities. Japanese engineers urgently needed an admixture that could dramatically increase flow without sacrificing strength or requiring excessive cement. This was a classic pain point: the construction industry had “no material solution” to produce highly flowable yet low-water concrete, and the existing admixture chemistry had hit a wall. It was in this climate that a bold new idea took root.

Dormant Concepts Awaiting a Breakthrough

Polymer scientists had long known that novel water-soluble polymers might disperse cement better. In fact, the concept of using comb-shaped polymers – large molecules with a charged backbone and long side chains – was floating around in academic literature. But until the late 1970s, no one had successfully applied this to concrete. Researchers at Nippon Shokubai, a Japanese chemical company, began experimenting with new polymer structures for cement dispersion. They first tried polystyrene sulfonate (pSA), a polymer that had dispersing ability, but it alone was insufficient [2]. The real breakthrough came when they tried a copolymer: by grafting a second component onto the backbone, they created a “comb” polymer that radically improved dispersion [2]. Those lab experiments produced the first inklings of a new class of admixture that would later be called polycarboxylate ethers. The stage was set for a discovery that would solve the impasse.

The Scientific Breakthrough: Inventing the Comb-Shaped Superplasticizer

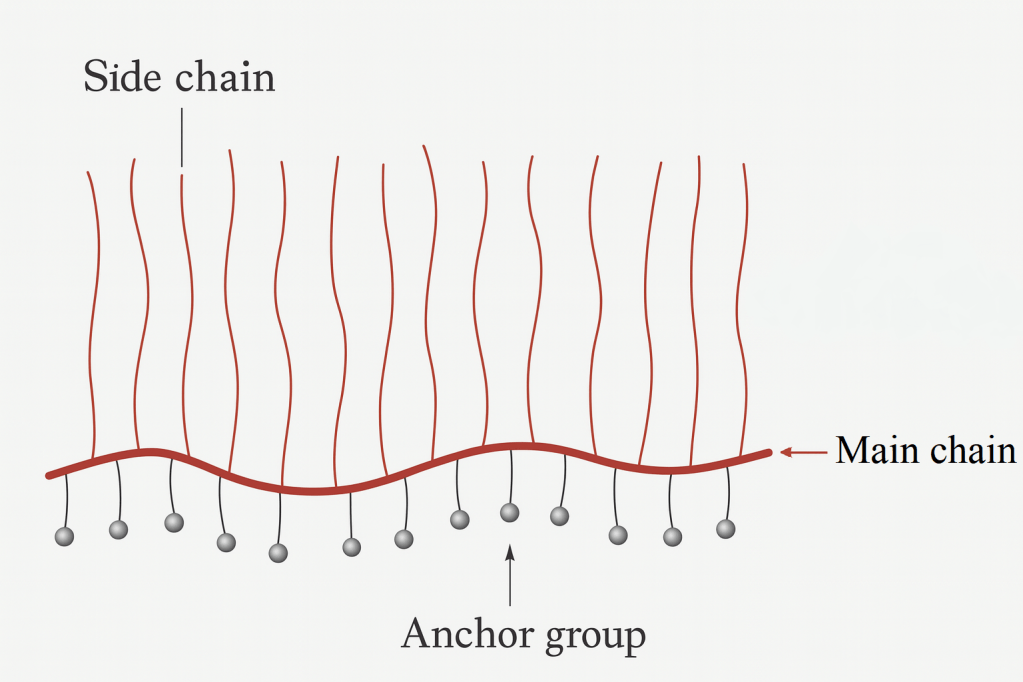

In 1981, Dr. Tsuyoshi Hirata at Nippon Shokubai achieved the decisive breakthrough: he invented the first true polycarboxylate ether superplasticizer [2]. Hirata’s invention was essentially a polymer tailored for cement: it featured an anionic “polycarboxylate” backbone that could anchor onto cement particles, plus an array of long polyethylene glycol side chains that extended into the mix water [[3]].

Comb-shaped PCE superplasticizer

This comb-like architecture proved revolutionary. When added to a concrete mix, the negatively charged backbone sites would adsorb strongly onto the positively charged calcium-rich surfaces of cement grains [2]. Once attached, the polymer’s many flexible side chains radiated outward – like the spines of a chestnut burr – creating steric repulsion between cement particles [[4]]. Cement grains that would normally clump together were now kept dispersed by this molecular “hairbrush.” The result was extraordinary: with the new admixture, concrete could achieve the same flow with 40% less water compared to mixes without admixture [2]. Equally important, the dispersion was more stable over time – slump loss (the gradual stiffening of fresh concrete) was dramatically reduced, since the polymer’s physical hindrance prevented particles from re-flocculating quickly. Dr. Hirata reported that this novel superplasticizer not only improved workability and lowered water/cement ratio, but did so cost-effectively and even enhanced strength development [2]. In short, the comb polymer concept cracked the code, achieving what earlier admixtures could not: very high water reduction combined with sustained workability and compatibility.

Chemistry and Molecular Engineering of PCEs: The genius of the polycarboxylate ether design lies in its tunable structure. A typical PCE molecule consists of a backbone built from acrylic or methacrylic acid units (providing carboxylate (-COO⁻) groups for anchoring to cement) and side chains of poly(ethylene oxide) or similar ether chains that are grafted along the backbone [3] [[5]]. This is made by a “macromonomer” synthesis: a long polyether side chain with a reactive vinyl end-group is co-polymerized with acid monomers, forming a comb copolymer in one step [5]. By adjusting the length of side chains, the number of side chains, and the backbone charge density, chemists could fine-tune the polymer’s performance. For example, longer side chains generally increase the steric hindrance effect and improve slump retention, while a higher density of carboxylate groups increases initial dispersion power [3]. Early PCEs (circa 1981–85) were often made with methoxy-polyethylene glycol methacrylate (MPEG) macromonomers – yielding an ester-linked comb polymer [5]. These gave excellent water reduction but sometimes could cause slight cement hydration delays. Over time, new macromonomers were developed: allyl PEG (APEG), hydroxypropyl PEG (HPEG), isopentenyl PEG (IPEG), and even vinyl ether-based PEGs (VPEG) [5]. Each variation offered tweaks to performance – for instance, HPEG and IPEG types (with certain pendant structures) became popular for their cost-effectiveness and high slump retention [2]. The key was that PCE chemistry proved remarkably designable: rather than a one-size-fits-all additive, it could be a whole family of tailored polymers optimized for different cements, temperatures, or performance needs [3] [5]. This molecular engineering capability has been crucial to PCE’s widespread success.

Mode of Action – Steric Hindrance vs Electrostatic Repulsion: Earlier sulfonate-based superplasticizers (SNF, SMF) worked mainly by coating cement with negatively charged sulfonate groups, creating electrostatic repulsion between particles. PCEs introduced a dual mechanism: the anionic backbone still gives electrostatic repulsion, but the big game-changer is the steric hindrance from side chains [2] [4]. Imagine cement grains surrounded by bristling polymer brushes – they simply cannot get close enough to stick together. This steric effect is less sensitive to ions in the mix water (which often compress the electrostatic charges in sulfonate admixtures) and thus is more robust in real concrete conditions. The outcome is a dramatic improvement in dispersion stability. PCE’s comb polymers keep cement grains apart even as the cement begins hydrating, whereas older superplasticizers would often be neutralized or absorbed quickly, allowing flocculation to resume. This explains why PCEs can maintain slump and fluidity for hours in properly designed formulations, compared to 30–60 minutes for naphthalene-based products under similar conditions. Furthermore, PCEs are effective at much lower dosage: one advanced PCE product (Sika ViscoCrete®) claims to achieve the same effect at one-tenth the dose of earlier superplasticizers [1]. This efficiency not only cuts cost per cubic yard of concrete, but also reduces the risk of admixture side effects (since less chemical is introduced). And unlike formaldehyde-condensed melamine or naphthalene admixtures, PCEs are synthetized without toxic ingredients – no formaldehyde or ammonia release in use [1]. In sum, the comb-shaped PCE ushered in a new mechanism of action that unlocked unprecedented performance in concrete mixing.

From Lab to Market: Early Commercialization and Adoption

Inventing PCE in the lab was only half the battle; the next challenge was convincing a traditional industry to adopt this novel polymer. Nippon Shokubai filed patents and began scaling up production of PCE in the early 1980s [[6]]. By 1986, the company had introduced the first commercial PCE-based superplasticizer in Japan (often referred to as an MPEG-type PCE) for use in concrete [[7]]. Branded products soon followed – one early trade name was Mighty®, a superplasticizer that became synonymous with high-flow concrete in Asia. Japanese contractors were quick to leverage the new admixture on challenging projects: high-rise construction and long-span bridge builds in the late 1980s saw concrete mixes reaching strengths and fluidity previously unattainable. For example, Japan’s first self-compacting concrete (SCC) trials in the late 1980s, aimed at eliminating vibration work, relied on PCE to achieve self-flow without segregation. By the early 1990s, SCC – enabled by PCE – was being used in Japanese precast factories to produce flawless architectural concrete with far less labor. These successes at home spurred interest abroad.

Entry into Europe and Beyond: European admixture companies and researchers caught on to the comb-polymer concept by the mid-1980s. In fact, European scientists introduced PCE superplasticizers by the 1980s, recognizing that the new polymers combined electrostatic and steric dispersion in one package [[8]]. Companies like Sika (Switzerland), BASF (through its Master Builders acquisition in Germany/US), and Mapei (Italy) began developing their own PCE admixtures as patents allowed or via licensing. By the late 1990s, a wave of third-generation superplasticizer products hit the global market: Sika’s ViscoCrete® line, BASF’s Glenium® series (formerly MasterGlenium), Grace’s ADVA® range, among others. These were all PCE-based formulations, each tuned for different applications (some for ready-mix slump retention, some for precast rapid strength, some for SCC, etc.). The commercialization in the early 2000s was rapid and widespread – essentially a global race to switch from older naphthalene admixtures to PCEs. As one industry publication noted in 2003, “the third generation superplasticizers are transforming concrete practice, making high-slump, high-strength concrete a routine option rather than a laboratory curiosity.” By 2007, PCE-based admixtures had become industry standard for any high-performance concrete application [3].

Major admixture producers consolidated around PCE technology, often highlighting it in flagship projects. For instance, the record-breaking Burj Khalifa tower (completed 2010) used PCE-based admixtures to pump high-strength concrete nearly 600 m vertically to the top. In Europe, the massive foundations of “The Shard” skyscraper (London, 2012) were cast using BASF’s Glenium, which allowed the concrete to remain workable for hours and be pumped to great heights [4]. Infrastructure projects like the Rion-Antirion Bridge in Greece and the Akashi Kaikyō Bridge in Japan employed PCE-admixture concrete for durable, dense high-strength elements. These early successes provided powerful case studies that accelerated market acceptance. By the 2010s, PCE superplasticizers had largely displaced the older sulfonate plasticizers in most concrete markets worldwide [3]. In regions like China – which saw a construction boom – PCEs were adopted swiftly in the 2000s and local production ramped up, making China one of the largest consumers and producers of PCE polymers by volume.

The Chemistry Behind PCEs: Why the “Comb” Made Concrete Flow

Polycarboxylate ether superplasticizers are, in essence, comb-shaped polymer surfactants designed specifically for cement. Their anionic polycarboxylate backbone strongly adsorbs to cement particle surfaces, while multiple nonionic polyethylene glycol (PEG) side chains stick out into the surrounding water [3]. This unique structure gives PCEs a three-fold advantage over earlier admixtures:

- Powerful Dispersion via Steric Hindrance: The PEG side chains create a thick, hydrated layer around each cement grain, physically preventing particles from approaching each other closely [4]. This steric repulsion keeps the cement uniformly dispersed and fluid. Traditional lignin or sulfonate admixtures lack significant side chains, so they rely purely on charge repulsion which is easily overcome as soon as some hydration products form. PCE’s comb architecture thus sustains dispersion far longer and at lower dosages.

- High Water-Reduction Capability: Because PCEs disperse cement so effectively, they liberate the water that would normally be trapped in cement flocs. This means one can achieve a given workability with significantly less water. Concrete mixes with 30–40% water reduction are routinely achieved using PCEs, compared to ~10% with lignosulfonates or ~20% with naphthalene sulfonates [1] [2]. Lower water content directly translates to higher strength and density in the hardened concrete. PCE-admixed concretes reaching compressive strengths of 80–100 MPa (12–15 ksi) became feasible without exotic materials – simply by enabling low water-to-cement ratios.

- Molecular Customizability and Compatibility: PCE polymers can be synthesized in myriad forms (different chain lengths, functional groups, charge densities), which means their interaction with different cements and supplementary materials can be optimized [3] [5]. For example, certain PCE formulations are designed for high sulfate cements or fly ash blends to mitigate compatibility issues (sulfate ions can otherwise compete for adsorption sites) [3]. Others are formulated for extended slump life – using slower-adsorbing polymer structures to keep concrete fluid for 2+ hours (vital for long-haul ready-mix deliveries in hot climates). This tunable chemistry has allowed PCEs to work synergistically with modern concrete practices, from high-volume mineral admixtures (fly ash, slag) to new cement chemistries, in a way older admixtures could never achieve.

Table 1: Competitive Landscape – Water-Reducing Admixtures Before vs. After PCE

| Category of Plasticizer | Era & Examples | Typical Water Reduction | Key Limitations |

| First Generation – Lignosulfonates | 1930s onward; Calcium or Sodium Lignosulfonate [1] | ~5–10% [1] | Modest effectiveness; can delay set; high dosage needed; limited improvement in high-strength concrete |

| Second Gen. – Sulfonated Melamine & Naphthalene (SMF/SNF) | 1960s–1980s; e.g. Melamine formaldehyde resin, β-naphthalene sulfonate [1] | ~15–25% [1] | Short slump retention (rapid workability loss); sensitive to temperature; compatibility issues with other admixtures [1]; contains formaldehyde (health/environment concerns) [1]. |

| Third Gen. – Polycarboxylate Ethers (PCEs) | 1980s onward; e.g. MPEG, APEG, HPEG types (ViscoCrete®, Glenium® etc.) [1] [2] | ~30–40% [2] | Highly effective, but can be sensitive to clays in aggregates and some cements (requiring tailored formulas) [2]; higher material cost (polymer production); “sticky” consistency in ultra-low water mixes (UHPC) [2]. |

As shown above, PCE superplasticizers hit a sweet spot that earlier admixtures couldn’t. They combine the best aspects of dispersing power and long working time, enabling a level of concrete performance that made them essentially no direct competition after introduction. Older products quickly became niche or obsolete for high-performance applications once PCEs arrived on the scene. Even in the basic ready-mix market, the ability to use one tenth the dosage to achieve the same slump made PCEs economically attractive despite higher per-unit cost [1]. Moreover, PCEs answered growing environmental and health demands: unlike sulfonated melamine/naphthalene admixtures, PCEs are formaldehyde-free and do not emit pungent odors like ammonia on contact with alkaline cement [1]. By the 2010s, no other admixture technology could rival PCE’s combination of efficiency and performance, and nearly all high-range water reducers sold were based on PCE chemistry [3].

Tension Rises: Challenges in Scaling and Implementation

Despite their clear technical superiority, PCE superplasticizers faced several challenges on the road to widespread commercialization:

- Manufacturing Scale-Up and Cost: Producing PCE polymers in bulk required investment in new chemical manufacturing processes. Early PCEs (MPEG type) were made via controlled radical polymerization with precise conditions to get the right molecular architecture. Ensuring consistent quality – so that every batch of admixture performed the same in concrete – was non-trivial. Initially, PCE’s raw materials (like polyethylene glycol) were more expensive than the chemicals for naphthalene admixtures. Could companies scale the process economically? This question loomed large in the 1980s. Over time, as demand grew, economies of scale improved and new synthesis routes were developed (including more efficient catalysts and even photopolymerization methods [[9]]). By the 2000s, cost had come down significantly, but even today PCEs remain pricier per kilogram than lignos or SNF – a challenge mitigated by their lower required dosage.

- Conservative Market and User Trust: The construction industry is famously cautious about new materials. In the late 1980s, convincing engineers and contractors to adopt a completely new admixture was not automatic. Would this strange new polymer have unintended side effects? Would it cause strength regressions or durability issues? Early adopters in Japan had positive results, but broader acceptance needed more field data. There was also skepticism: some ready-mix suppliers had grown comfortable with their naphthalene admixtures and didn’t see a need to switch unless forced. Education and demonstration were key – admixture companies had to show through projects and trial mixes that PCEs delivered on their promises (and that using them didn’t require dramatic changes in mix design aside from reducing water). By the early 2000s, enough high-profile successes (SCC in precast plants, HPC in tall buildings, etc.) had occurred to turn the tide of opinion in favor of PCEs.

- Workability and “Sticky” Concrete: As PCE-admixtured concretes with very low water content became common, a new issue emerged: sticky rheology. Contractors discovered that some PCE-high range mixes, especially those nearing 0.30 w/c ratio or containing high fines (like silica fume or very fine sand), exhibited a viscous, honey-like consistency – the concrete was fluid but didn’t “flow” as rapidly as expected, sticking to surfaces [3]. This is now understood as a problem of high plastic viscosity; essentially the mix has low internal lubrication despite high slump. It is particularly noted in ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) mixes. Researchers found that while PCE keeps particles dispersed, at very low w/c the depletion attraction and high solids content can lead to a different kind of cohesion. Solutions have included using viscosity modifiers and adjusting PCE structures. For instance, one approach has been using phosphate-functionalized PCEs or combining PCE with small amounts of other dispersants to mitigate stickiness [2]. The issue remains an active area of innovation, especially as UHPC and printable concrete grow.

- Sensitivity to Clays and Contaminants: One of the most notorious challenges for PCE superplasticizers is their sensitivity to certain types of clay present in aggregates or cement replacements. Tiny amounts of swelling clays (like montmorillonite) can adsorb PCE molecules or disrupt their function, causing an unexpected loss of slump or need for higher dose [2]. This was less of an issue with older admixtures like SNF, which were used at higher dose and had simpler mechanisms. The PCE industry responded by developing specialized “clay tolerant” PCEs – often with modified side chains or incorporating sacrificial agents that preferentially bind to clay [2]. Nonetheless, variability in sand or aggregate clay content in the field can still pose problems. Concrete producers have learned to test new material sources for compatibility or use supplementary admixtures (like slump stabilizers or clay mitigators) when necessary. The quest for a perfectly clay-insensitive PCE continues in research labs; for example, introducing bulky side chains or charged surfactants to prevent clay intercalation has shown promise, but no silver bullet has yet been found [2].

- Adapting to New Cements and Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs): As the concrete industry moves towards greener materials (blended cements with calcined clays, fly ash, slag, or even alkali-activated binders), PCE admixtures must adapt. Each of these novel binders presents a different chemical environment. For instance, calcined clay (as in LC3 – Limestone Calcined Clay Cement) increases water demand and adsorbs admixtures differently due to its high surface area and chemical makeup [2]. Standard PCEs that work in OPC might underperform with high clay blends, leading to lower than expected slump or higher viscosity [2]. Similarly, alkali-activated slag (geopolymer concrete) typically has a very high pH activator solution in which many PCEs are insoluble or ineffective [2]. Admixture companies are actively developing new PCE structures to address these challenges – for example, PCEs that remain soluble in alkali activators, or have particular charge profiles that better suit calcined clay mixes [2]. This is both a challenge and an opportunity: PCE’s basic design is flexible enough that, with some molecular tweaking, it can likely be made to work for these next-generation “low clinker” concretes. The ongoing innovation in PCE chemistry will be pivotal in the industry’s push to reduce cement CO₂ footprint [2].

- Higher Polymer Content and Curing Effects: Using much less water in concrete (thanks to PCE) means hydration chemistry can differ. Early high-strength concrete adopters noticed that some PCE-admixed concretes had slightly slower early strength gain, likely due to the lower water and perhaps slight retardation from polymer adsorption. There were also concerns: would the presence of polymer (often a few hundred grams per cubic meter) affect long-term properties like creep, shrinkage, or durability? Extensive testing has largely allayed fears – PCEs are mostly inert in the hardened concrete and many studies show equal or improved durability due to the reduced porosity from lower water content [2]. In fact, a rational use of PCE can significantly improve durability indicators (like lowering permeability and increasing electrical resistivity of concrete by over 100% in some cases [2]). Nonetheless, best practice dictates optimizing dosage: too high a PCE can cause excessive air entrainment or segregation (if the mix gets too fluid), so producers learned that “just enough to achieve the target slump” is ideal.

These challenges added real suspense to the PCE innovation story: the science was sound, but would the technology clear the hurdles of manufacturing, economics, and on-site performance to achieve global success? By the early 2000s, the answer was becoming clear: yes, it would.

Competitive Landscape Before and After PCE

Before the advent of PCE superplasticizers, concrete technologists had to choose among imperfect options for high-workability concrete, each with major drawbacks. Plastic-covered mixes using only lignosulfonates could only go so far – to get very fluid concrete, one had to dilute with water (sacrificing strength) or accept significant set retardation from overdosing lignin. The sulfonated melamine and naphthalene superplasticizers of the 1970s–90s finally allowed flowing concrete without extra water, but these mixes were finicky. High-range admixture dosages often caused rapid slump loss – workers had to rush to place concrete before it stiffened [1]. At times, contractors would “re-temper” with water on site, negating the water reduction benefits. Temperature made a big difference: in hot weather, an SNF-plasticized mix might lose nearly all slump in 30 minutes, leading to complaints and rejections. Compatibility with cements was another headache; a brand of superplasticizer might work well with one cement but cause another cement to flash set or develop unexpected gel particles (due to interactions with soluble alkalis or gypsum). These inconsistencies undermined confidence. No material hit the sweet spot of providing high fluidity, extended workability, and strength gain without downsides – until PCE arrived.

After PCE superplasticizers were introduced (post-1980s), the landscape changed dramatically. The older generations began to phase out for most structural concrete purposes. Naphthalene and melamine admixtures, once ubiquitous for pumping concrete or precast, saw declining use, remaining only where their very short action might be desirable (e.g. some precast plants where fast slump loss can be tolerated or where cost is paramount in low-end applications). New competitors to PCE? Essentially, PCE itself became a broad platform for competition – companies competed on whose PCE had better slump retention or whose could tolerate more clay, etc., but there was no wholly different class of superplasticizer that could outperform the comb polymer. A few alternatives have been studied, like polyphosphonates or succinic anhydride co-polymers, but none achieved the commercial impact of PCE. Instead, PCE technology continued to evolve: new variations like phosphate-modified PCEs (to improve early strength and robustness) and even zwitterionic PCEs (polymers containing both positive and negative groups to improve compatibility) have been developed [2]. Competitors that emerged in the 2010s were often just other companies’ PCE products. For instance, Corning’s Gorilla Glass had Dragontrail and Xensation as rival tough glasses, but in the admixture world, virtually every major admixture brand converged on PCE as the solution, just with different trade names and incremental innovations. To this day, polycarboxylate ethers remain the state-of-the-art high-range water reducer, with continuous refinements but no fundamental replacement on the horizon.

The Breakthrough Moment: PCE Goes Mainstream

It’s hard to pinpoint a single date when PCE “broke through,” since it was a gradual uptake globally. However, one can highlight the late 1990s to early 2000s as the turning point. This was when multiple tipping factors converged:

- Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC) – Proof of Concept: In 1988, Japanese researchers (Okamura et al.) developed SCC, a concrete that could flow under its own weight and fill forms without vibration. This revolutionary concept was made practical only by using PCE superplasticizer to obtain high flow at a moderate water content. Through the 1990s, SCC spread to Europe, proving in real projects (like the Swedish bridge at Ölandsbron in 1995, and extensive use in Danish precast by late 90s) that PCE-admixed concrete could maintain workability for long periods and produce superior surface finish. SCC’s success was in many ways PCE’s breakthrough application, showcasing abilities no other admixture could achieve.

- High-Profile Mega Projects: The early 2000s saw an unprecedented boom in supertall buildings and extreme engineering projects – Petronas Towers (Malaysia, 1998), Three Gorges Dam (China, ~2003), Viaduc de Millau (France, 2004), Burj Khalifa (UAE, 2004–2010), to name a few. In virtually all these projects, PCE-based admixtures were the enabling technology for the concrete mix designs. When the Burj Khalifa’s record-breaking 80 MPa high-performance concrete was pumped 600 meters vertically, it was Glenium (BASF’s PCE admixture) that made it possible. Such headline-grabbing feats demonstrated to the world that PCE admixtures were not just lab curiosities but mission-critical components of modern construction. Builders of less extreme projects took note – if PCE works for the tallest tower or longest bridge, it can work for our everyday high-rise or highway.

- Global Industry Adoption and Standardization: By 2000, leading admixture companies had aligned behind PCE. In 2001, Sika rolled out ViscoCrete globally, and Master Builders (later BASF) launched Glenium in North America and Europe. Industry standards bodies and researchers also shifted focus – new European norms and ASTM standards recognized the new admixture type (often calling them “Type F high-range water reducers (polycarboxylate)”). The fact that multiple suppliers were offering PCEs also reassured customers that it wasn’t a single-source risky new thing, but rather the future of admixtures. Ready-mix companies started switching their default high-range admixture to PCE around this time. In some regions, government projects began specifying “third-generation superplasticizer” for high-performance concrete bids, effectively mandating PCE use. All these signs pointed to a full market transition in progress.

One could say the “iPhone moment” for PCE superplasticizers was when self-consolidating concrete and high-performance concrete went from niche to mainstream around the early 2000s, and PCEs were at the heart of that shift. After that, there was no looking back – PCE-based admixtures rapidly became the industry standard for any demanding concrete work [3]. The technology had found its perfect application and timing.

Why PCE Superplasticizers Succeeded: Keys to Widespread Commercialization

Looking at the situation by the mid-2000s (without hindsight beyond that point), several factors stand out as indicators that PCE superplasticizers were poised for sustained technical and commercial success:

- Clear Market Need: By the 1990s, concrete construction was pushing boundaries that older admixtures could not handle – higher strength requirements, pumping to greater heights, more congested reinforcements requiring flowing concrete, and faster construction cycles. There was a pressing need for an admixture that could deliver high workability without compromising strength or durability. PCEs directly answered this need. As one review noted, PCEs can reduce water demand by up to 40% without loss of workability, enabling far stronger and more durable concrete [2]. This kind of performance leap was exactly what the market was hungry for. The strong pull from the market meant that if the technology could deliver reliably, it would be eagerly adopted.

- Technical Superiority and Robustness: Technologically, PCE superplasticizers proved their merit in concrete after concrete. They not only provided greater water reduction and slump retention, but did so with a level of consistency and predictability that won over engineers. Field trials showed that PCE-admixtured concrete could be transported longer distances and still placed easily, a big advantage for urban areas where batching plant locations are limited. Importantly, PCEs improved concrete’s hardened properties – higher 28-day strengths, lower permeability, improved finish – fulfilling the promise of “high performance” concrete in practice [2] [4]. This technical validation built confidence. At trade conferences and in academic papers, early adopters presented data of PCE mixes achieving, say, 30 MPa (4350 psi) in 24 hours or 100+ MPa in 91 days, or producing beautiful architectural pours with zero vibration. The steric hindrance mechanism also made intuitive sense to concrete technologists, helping alleviate concerns: it was a straightforward physical effect, not a complex chemical byproduct that might unpredictably interfere with cement hydration (indeed, studies showed PCEs caused no significant changes in hydration products aside from the intended workability effects [3]).

- Industry Commitment and Expertise: The development of PCE superplasticizers benefitted from being championed by established, technically strong companies. Nippon Shokubai, and later major players like Sika, BASF, Grace, and Mapei, had deep R&D resources and reputations at stake. They invested in optimizing PCE formulations and educating the market. For instance, Sika and BASF spent heavily on technical teams that traveled to job sites to ensure successful initial applications of SCC and PCE-based mixes, essentially shepherding the technology into routine use. By resurrecting and enhancing a 1980s Japanese invention, these firms showed commitment. The global manufacturing capacity was ramped up in advance, ensuring supply could meet demand as it grew. Patents that expired (the original Hirata patents likely lapsed by the early 2000s) opened the field for even more producers, spurring healthy competition and further innovation. In short, if anyone could pull off a worldwide shift in concrete admixtures, it was these industry leaders, and they did.

- Early Validation in Niche But Influential Applications: The initial successes of PCE were often in critical, high-performance niche applications – like precast concrete elements with intricate shapes, or high-strength columns for landmark buildings. While these weren’t the bulk of concrete volume, they acted as influential case studies. When the precast industry demonstrated that using PCE admixtures could cut vibration effort (thanks to self-compacting mixes) and speed up production (due to higher early strength from low water/cement), the news spread quickly through industry circles. Likewise, when infrastructure owners saw that PCE-enabled concrete could incorporate 50% supplementary cementitious materials like fly ash or slag and still reach high strength, it aligned with their durability and sustainability goals [4]. These pre-2005 validations served as strong signals that PCE was not a risky gamble but rather a proven improvement poised to become mainstream.

- Synergy with Sustainability Trends: Although not the initial driver, PCE superplasticizers arrived at a time when the environmental impact of concrete was coming under scrutiny. By the 2010s, the push for green building and CO₂ reduction in cement was in full swing. PCEs turned out to be an enabler for sustainability: by allowing significant water and cement reduction for the same performance, they indirectly reduce the carbon footprint of concrete. Moreover, as BASF highlighted, admixtures like Glenium made it feasible to replace up to 50% of Portland cement clinker with industrial waste supplements (fly ash, slag) while maintaining strength – leading to as much as 60% carbon emission reduction in the concrete [4]. This concept, branded as “Green Sense Concrete” by BASF, showed that high-performance admixtures could contribute to LEED points and other green certification criteria [4]. In summary, PCEs found themselves on the right side of sustainability history, further cementing (no pun intended) their importance in the future of construction.

In combination, these factors created a powerful momentum that propelled PCE superplasticizers to global dominance in the admixture market. By 2020, it was estimated that PCE-based admixtures accounted for the vast majority of high-range water reducers used worldwide, a testament to the success signals that were evident decades prior.

Impact: High-Performance Concrete and the Infrastructure Boom

The ripple effects of PCE superplasticizer technology on the construction industry have been profound. High-Performance Concrete (HPC), once a specialized research topic, became a practical reality largely due to PCE admixtures. Concrete mix designs in the 1970s rarely exceeded 40–50 MPa (6000–7000 psi) compressive strength; by the 1990s, mixes of 100 MPa (15,000 psi) or more were routinely achieved for columns and cores of skyscrapers – many using PCE to get there. This strength jump enabled the rise of super-tall buildings by reducing column sizes (less dead weight) and allowing innovative structural systems. The Petronas Towers (452 m, opened 1998) and Taipei 101 (509 m, opened 2004) both utilized advanced superplasticized concretes for their high-strength lower floors. Today’s tallest, the Burj Khalifa (828 m), simply could not have been built with concrete without the extreme workability and strength afforded by PCE admixtures. The ability to pump concrete vertically hundreds of meters without it setting or losing slump is directly attributable to PCE’s slump retention and dispersive power [4].

Infrastructure and Transportation: Bridges, tunnels, and roads also saw major benefits. The use of flowable yet low-water concrete has improved the quality of bridge decks and highway pavements, which are now less prone to cracking and have longer life due to lower permeability. PCE admixtures facilitated mass pours (like large mat foundations or dam sections) by allowing mixes that generate less heat (because of less cement) and remain workable longer, reducing cold joint risks. In precast tunnel segments (for subways or sewer systems), self-compacting concrete with PCE sped up production and achieved better surface quality, minimizing repairs. All these improvements accelerated the pace at which infrastructure could be built and improved its longevity – effectively helping societies do more with concrete in less time.

Advances in Construction Methods: PCEs also unlocked new methods and concrete types. One example is self-consolidating concrete (SCC), which has been widely adopted for precast elements, building columns, and even cast-in-place walls where rebar congestion is high. SCC, made possible by PCE, eliminates the need for vibration, reducing labor, noise, and improving the finish. Another area is architectural concrete – high flow mixes that can create smooth, intricate surfaces with minimal bugholes. PCE’s dispersing ability ensures uniform color and texture, which architects love for exposed concrete designs. In recent years, 3D printed concrete (additive manufacturing of concrete components) has emerged; these printable mixes rely on admixtures (including PCE variants) to achieve a mix that is both extrudable and shape-holding – a delicate balance of flow properties influenced by polymers.

Global Construction Trends: The broad availability of PCE superplasticizers leveled the playing field in concrete technology. Developing countries could leapfrog to state-of-the-art concrete by importing or locally producing PCE admixtures, without going through decades of incremental admixture development. This contributed to the rapid urbanization seen in parts of Asia and the Middle East in the 2000s–2010s – ambitious projects could be realized in places that a generation prior had only basic concrete technology. Moreover, PCEs helped in meeting modern building codes and standards that demand performance concrete. For example, high-rise construction codes often require pumping and placing concrete at high slumps to ensure quality; PCE makes this routine. Green building standards like LEED and BREEAM encourage use of materials that reduce resource consumption – as noted, PCE-admixtured mixes can save cement and water, contributing to points for sustainable materials [4].

On the environmental side, PCE’s impact is double-edged. Positively, it enables cement reduction and substitution, which directly cuts CO₂ emissions from cement production [4]. A study by BASF calculated that their PCE admixtures used in 2008 saved 22 million tons of CO₂ via enabled cement substitution – equivalent to the yearly emissions of a city like Berlin [4]. This is a massive contribution to sustainability. On the other hand, one must acknowledge that PCE polymers themselves have a carbon footprint (they are petroleum-derived, requiring chemical processing). When used at low dosages, this is negligible compared to cement’s footprint, but as mixes evolve (e.g., ultra-high strength concretes with lots of polymer or low-clinker binders needing more admixture), the balance will be watched. Still, the net environmental impact of using PCE in concrete is overwhelmingly positive when it enables large cement reductions [2].

Continuing Innovations and Future Outlook

Far from being a static technology, PCE superplasticizers continue to evolve in response to new challenges. Researchers and chemical companies are pursuing several promising directions:

- Enhanced Clay Tolerance: As mentioned, clay contamination in aggregates can sap the effectiveness of PCEs. New comb polymer designs are being explored that include sacrificial anionic sites or novel anchoring groups that preferentially bind to clay, preserving the main dispersion function for cement. For example, one approach introduces zwitterionic groups or cationic segments in the PCE that can neutralize clay surfaces without ruining the polymer’s ability to disperse cement [2]. Another approach is adding a small percentage of specialty surfactants alongside PCE to “shield” it from clay. Future PCE admixtures will likely be advertised as “high clay tolerance” to address the increasing use of manufactured sands (which often contain clays) and marginal aggregates.

- Admixtures for Low-Carbon and Alternate Binders: The next frontier is ensuring PCEs work with emerging low-CO₂ cements. This includes not only calcined clay blends and slag as discussed [2], but also limestone-rich cements, magnesia-based cements, and geopolymer systems. Each poses unique chemical environments (for instance, geopolymer activators can be highly alkaline sodium silicate solutions that would precipitate ordinary PCE). Custom polymers are being developed – for example, PCEs with higher acid content to remain soluble in high pH, or those with organosilane functional groups to better bond with slag or ash-rich systems [3]. The 2020s may see a diversification of the PCE family into sub-types specifically branded for these new binder systems. Given the concrete industry’s “mega transition” toward low clinker materials, PCEs are expected to play a pivotal role in making those new concretes workable [2].

- Multi-Functional Admixtures: Researchers are also experimenting with comb polymers that do more than just disperse. For instance, a PCE polymer was developed with calcium-chelating groups to also act as a mild set retarder for extended work times [3]. Others have incorporated air-entraining functions into a PCE to produce a stable air-void system in freeze-thaw resistant concrete while plasticizing it (thus simplifying admixture cocktails). There’s also interest in shrinkage-reducing PCEs – tweaking the side chain chemistry such that the polymer reduces capillary tension during drying. While none of these hybrid admixtures have huge market presence yet, they represent the modular potential of PCE chemistry – you can essentially “plug and play” functional monomers into the comb structure.

- Synthesis and Sustainability Improvements: On the manufacturing side, innovation continues to make PCE production greener and more efficient. Traditional PCE synthesis uses radical polymerization in solution, often requiring solvents or generating byproduct salts that need disposal. New methods like photopolymerization at room temperature [9] or continuous reactive extrusion are being studied to reduce energy and waste. There is also movement toward bio-based raw materials for PCEs – for example, using bio-derived ethylene oxide for PEG chains, or exploring polysaccharide-graft polymers as a partial replacement. While polycarboxylate ethers today are petroleum-based, the future could see more renewable content, aligning with the construction industry’s sustainability goals.

- Tailoring Rheology for 3D Printing: As 3D printing of concrete (additive manufacturing) grows, admixtures will need to finely balance flow and yield stress (to allow extrusion but prevent collapse of layers). PCEs will be a part of that solution, likely in combination with viscosity modifying agents. Already, some PCE formulations are advertised for “rheology control”, giving not just flow but also a specific shear-thinning behavior suited to pumping or printing. The comb polymer can be designed to interact with viscosity modifiers or nano-particles to achieve the thixotropic response needed for new placement techniques.

In essence, the PCE superplasticizer is not a single product but a platform technology – one that continues to spawn new variants and uses. Its success over the last 40+ years provides a strong foundation to tackle the next era of concrete challenges. From enabling the highest skyscrapers to the greenest concrete mixes, the innovation story of PCE superplasticizers exemplifies how a breakthrough in chemistry can transform an entire industry. Polycarboxylate ethers took concrete, the world’s most used man-made material, and made it perform better, last longer, and meet the demands of a changing world – truly a quiet revolution flowing through every corner of modern infrastructure.

References

[1] Dr. M. Arnold „Function and history of polycarboxylate ether (PCE) in dry mortar and concrete“ L-I Concrete Admixtures Knowledge Center https://www.l-i.co.uk/knowledge-centre/function-and-history-of-polycarboxylate-ether-pce-in-dry-mortar-and-concrete/#:~:text=content,low%20compatibility%20with%20other%20additives

[2] L. Lei, T. Hirata, J. Plank, “40 years of PCE superplasticizers – History, current state-of-the-art and an outlook“ Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 157, 2022, p. 106826 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2022.106826

[3] A. Habbaba, A. Lange, J. Plank, „Synthesis and performance of a modified polycarboxylate dispersant for concrete possessing enhanced cement compatibility“, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., Vol. 129 (1), 2013, pp. 346-353 https://doi.org/10.1002/app.38742

[4] BASF Science Article“Building sustainably with concrete” BASF, ~2010 (Accessed Dec. 2025) https://www.basf.com/us/en/media/science-around-us/building-sustainably-with-concrete

[5] SureChemical Industry Article „About Polyether Macromonomers and PCE“ (Accessed Dec. 2025) https://www.surechemical.com/aboutus/About-polyether-macromonomers-and-polycarboxylate-superplasticizer-PCE.html#:~:text=amphiphilic%20properties%2C%20usually%20a%20polyoxyethylene,form%20the%20polycarboxylic%20acid%20backbone

[6] Nippon Shokubai Corporate Info „Third International Conference on Polycarboxylate Superplasticizers (PCE 2019), Held Sept. 24-25, 2019 at Technical University of Munich. https://www.shokubai.co.jp/en/news/201911287871/#:~:text=Presentation%20of%20a%20New%20Technology%2C,The .

[7] International Conference on Polycarboxylate Superplasticizers (PCE 2017) https://pce-conference.org/events/#:~:text=PAST%20EVENTS%20%E2%80%93%206th%20International,first%20time%20introduced%20this

[8] D. Breilly, S. Fadlallah, V. Froidevaux, A. Colas, F. Allais „Origin and industrial applications of lignosulfonates with a focus on their use as superplasticizers in concrete“, Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 301, 2021, p. 124065 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124065

[9] T. Zhou, Z. Li, H. Duan, Y. Tang, Y. Pang, H. Lou, D. Yang, X. Qiu, „Synthesis of Polycarboxylate Superplasticizers via Photoinitiated Radical Polymerization“, ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 8, 4818–4829 https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.4c00472

Leave a Reply