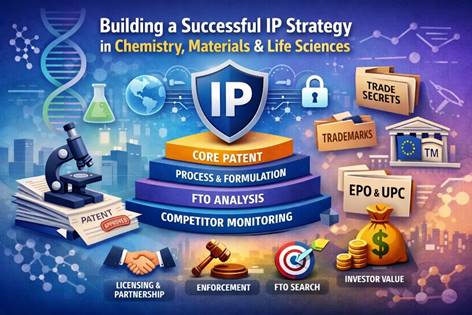

Focus on Chemistry, Materials & Life Sciences

You do not need a law degree to run R&D or a startup. You do need an IP strategy that is engineered like a good process: clear objective, defined inputs, robust controls, and a plan for failure modes. In chemistry/materials/life sciences, IP is often the core asset investors underwrite and partners pay for.

This is a practical, EU-anchored playbook (with global comparisons)

What “successful” means in IP strategy

A successful IP strategy does not mean “lots of patents.” It means you can repeatedly achieve one or more of these outcomes:

- Fundraising credibility: investors can see a defensible moat.

- Partnering leverage: you can license, co-develop, or sell with strong terms.

- Commercial protection: competitors cannot copy the revenue-driving features without pain.

- Freedom to operate (FTO): you can launch without stepping on landmines.

- Cost control: your spend is tied to value milestones, not vanity metrics.

A useful benchmark: EPO/EUIPO found that European startups that filed patents or trademarks early were up to 10.2× more likely to secure funding than those that did not.

1) Start with the business: “What are we protecting, for what purpose?”

In chemistry/materials/life sciences, your value usually sits in a stack, not a single invention:

- Core composition / biological construct (molecule, polymer, strain, vector)

- Manufacturing route (process steps, catalysts, purification, scale-up know-how)

- Formulation / delivery (stability, shelf life, device-interface)

- Use / indication / application (materials use-case, therapeutic indication)

- Analytics (assays, QC methods, reference data)

- Brand (name + positioning that survives beyond patent expiry)

Practical framing: map revenue to features. Then protect the features that (i) customers pay for and (ii) competitors can copy.

2) Choose the right IP types: patents, trade secrets, trademarks (and when)

Patents

Use patents when:

- the product can be reverse engineered (common in materials and small molecules),

- you need investor-grade defensibility, or

- you need to license (partners usually require patent families, not “trust us” slide decks).

Common pitfall (startup classic): filing a “cheap” initial application, then publicly disclosing the real details before the robust filing. Several biotech practitioners warn that a weak first filing plus later disclosure can destroy priority for crucial claim scope.

Trade secrets

Use trade secrets when:

- the advantage is in process know-how not visible in the product (e.g., purification parameters, catalyst conditioning, cell-culture tuning),

- the secret can be kept secret (access control + contracts + documentation),

- you want indefinite duration.

Downside: if a competitor independently develops it, you usually cannot stop them. (So secrets work best when replication is hard.)

Trademarks

Underused in deep tech. Trademarks:

- support pricing power and customer retention,

- can outlive patents,

- matter early for product naming and avoiding forced rebrands.

3) Filing strategy that fits scientific reality (EU-first, global-ready)

A) Treat “priority” as an engineered control point, not a formality

In EU practice, “file first, disclose later” is not optional. Europe largely lacks a broad grace period for your own disclosures; a premature publication can be fatal.

Actionable rule: the week you schedule a conference abstract, preprint, thesis deposit, public demo, or investor deck with enabling detail—assume you need a filing before it.

B) Use a “layered portfolio” rather than one heroic patent

In these sectors, value often comes from portfolio architecture:

- Core: composition/construct (or key material class)

- Moat: manufacturing route + key intermediates + purification

- Commercial edge: formulation/device interface/processing window

- Market fit: use claims by application segment (materials) or indication/combination (life sciences)

Investors like this because it reduces single-point failure (one patent attacked → business collapses).

C) Europe vs US: differences that matter operationally

- Disclosure timing: US has a limited grace period, but EU generally does not; global strategy should behave like EU.

- Claiming medical inventions: the US more readily uses method-of-treatment claim formats; Europe uses different claim formulations and exclusions for treatment methods (you draft differently).

- Post-grant attacks: Europe has centralized EPO opposition (a common threat in pharma/biotech); the US has PTAB proceedings. Plan budgets and claim strategies accordingly.

D) Europe’s evolving enforcement landscape (UP/UPC)

The EU’s Unitary Patent and Unified Patent Court create opportunities for broader, centralized enforcement (and centralized risk). Whether to use it is now a strategic decision for many portfolios.

4) Freedom to Operate and competitor monitoring: the part founders skip (and regret)

FTO (Freedom to Operate)

FTO is not “a search.” It is a claims-based risk assessment of active patents in target markets.

Why it matters: CAS notes that teams can spend years on a molecule or project only to find the space is an IP minefield and not commercially feasible.

Practical cadence:

- early “landscape scan” (cheap, directional),

- pre-pilot/scale-up FTO refresh,

- pre-launch FTO (markets + manufacturing hubs).

Typical outcomes:

- design-around,

- license-in,

- challenge (EPO opposition / observations),

- pivot application/indication.

Competitor monitoring

Patent monitoring is not paranoia; it is intelligence. The goal is to detect:

- new filings that could block you,

- expiring patents opening windows,

- licensing opportunities,

- shifts in competitor R&D direction.

Even modest startups can run this with alerts + quarterly review, ideally coordinated by counsel.

5) Enforcement and “monetization”: when IP becomes a revenue tool

Enforcement options sit on a spectrum:

- Quiet resolution (license offer / commercial negotiation)

- Cease-and-desist (signal seriousness)

- Opposition/invalidity (attack competitor patents)

- Litigation (injunction + damages, jurisdiction-dependent)

In life sciences, enforcement strategy must also consider reputational and pricing sensitivity. Patents are economically important (they support exclusivity and investment), but there are credible policy critiques around access and “evergreening.”

6) Real examples and what to learn

Example 1: CRISPR — why EU details can decide who “wins”

The CRISPR patent landscape illustrates how outcomes can diverge by jurisdiction. In Europe, key filings were lost due to priority/formalities issues, showing why EU process discipline matters. The fight also illustrates how fragmented rights can create licensing friction and slow adoption.

Learning: “Great science” is not enough; procedural mistakes in Europe can erase strategic advantage. This is precisely where a specialist adds disproportionate value.

Example 2: Startup “weak first filing” trap

Biotech practitioners highlight recurring damage where early low-detail filings followed by disclosure undermine later, stronger filings (priority breaks → prior art appears).

Learning: do not treat the first filing as a placeholder unless your disclosure discipline is flawless. Most teams are not flawless.

Example 3: Investor behavior (Europe)

The EPO/EUIPO startup financing study gives quantified evidence that early IP filings correlate with funding success—especially relevant in deep-tech where traction arrives late.

Learning: IP is not only “legal”; it is a financing instrument.

7) A compact build plan (what to do in the next 30–90 days)

Step 1 — IP inventory and business mapping (week 1–2)

- list innovations by “composition / process / formulation / use / analytics / brand”

- rank by revenue criticality + copyability

- decide protect-as-patent vs protect-as-secret for each

Step 2 — Landscape + initial FTO screen (week 2–6)

- keyword + competitor patent scan in target markets

- identify top 20–50 “blocking families”

- decide: avoid / license / challenge / design-around

Step 3 — Portfolio architecture (week 4–10)

- draft the “core + moat + commercial edge” filing plan

- align with development milestones and financing calendar

- decide jurisdictions (EPO + US usually, others by market/manufacture)

Step 4 — Governance (week 6–12)

- invention disclosure workflow

- disclosure policy (conference/paper/deck review)

- monitoring cadence (monthly alerts, quarterly review)

This is exactly the kind of structured, cross-functional work where a qualified IP specialist can properly guide you—not just by filing, but by designing the strategy, preventing priority accidents, and aligning IP spend with business milestones.

A candid note on “do we really need a specialist?”

In these sectors, the answer is typically yes, for three reasons:

- Technical drafting quality is everything (especially in chem/biotech where claim scope hinges on how you describe variants and experimental support).

- EU procedure is unforgiving on disclosure timing and priority formalities.

- Portfolio architecture (how families relate, where to file, when to divide/continue, how to defend) is strategic, not administrative.

You can and should stay commercially in control—but let specialists run the legal-engineering of the protection system.

Leave a Reply